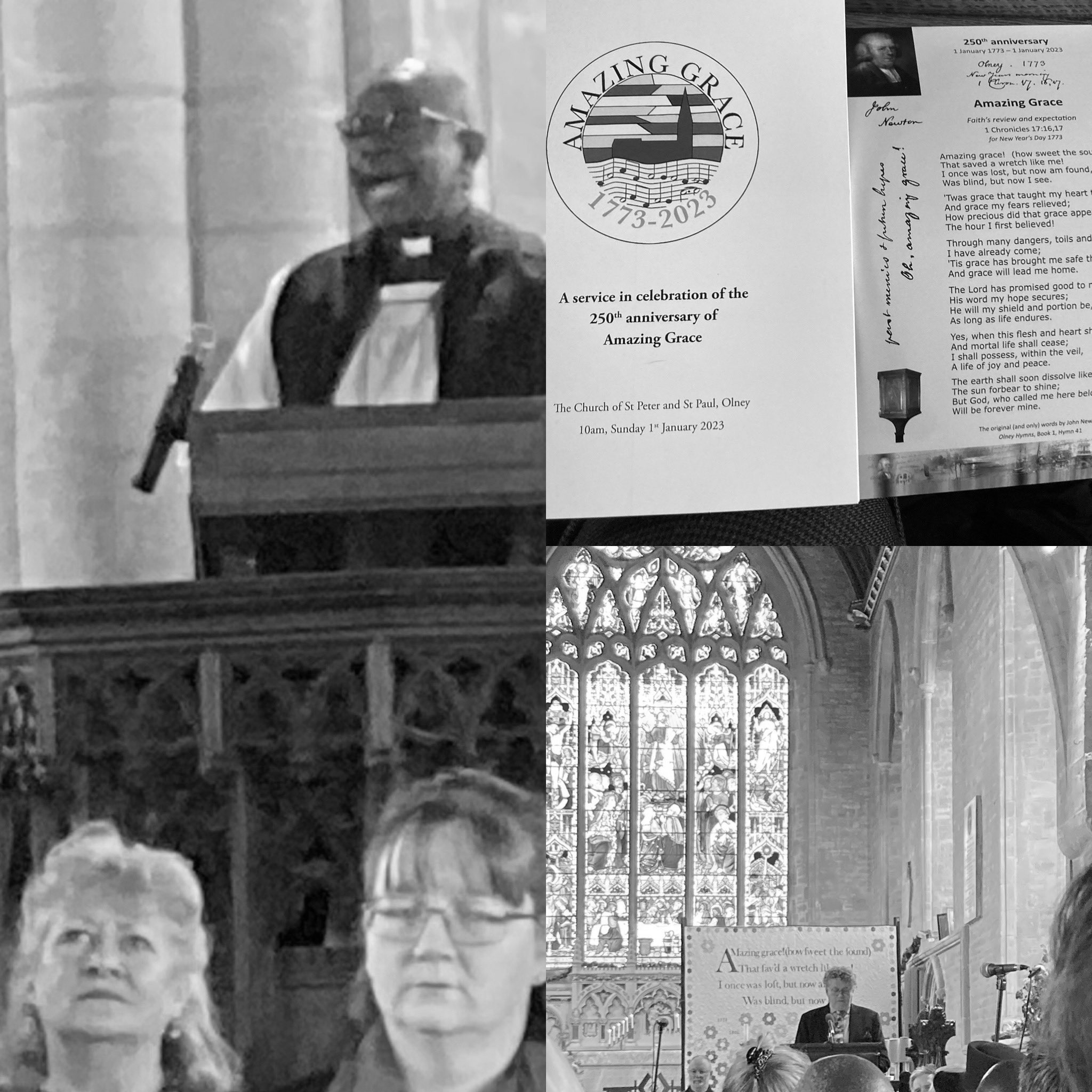

Exactly 250 years ago today, on 1st January 1773, the words of Amazing Grace were first heard here in Olney, Buckinghamshire. They were composed by the Reverend John Newton to accompany his sermon. In the following century, they were set to the tune we associate with Newton’s words.

The same judge who heard the Tobias Rustat case about, and in, Jesus College, Cambridge in 2022 had granted a faculty in 2021 to the Church of St Peter & St Paul, Olney, to present a more balanced account of Reverend John Newton ahead of today’s anniversary. Chancellor Hodge QC’s conclusion was that,

‘The planned changes to the eastern end of the south aisle of the church are designed to bring into regular and beneficial use what is presently a little-used area of the church and to ensure that it is available to educate visitors, in a balanced way, about John Newton, his life and his work, and to celebrate his later, and worthy, achievements whilst not overlooking or in any way seeking to diminish his earlier sins. The proposals will enhance the significance of the church through its strong connections with John Newton; and they will have no adverse or negative impact upon the significance of the church building. The four pews that will be removed are of no intrinsic, practical, or historical significance; and they will not be lost to the church. Rather, the proposals are entirely positive in terms of their impact. As the ‘Home of Amazing Grace’, with significant connections with John Newton and William Cowper, the church already attracts thousands of visitors every year; and the changes that are being proposed will only serve to enhance the visitors’ experience, thereby enhancing the church’s mission. The new displays will serve to remind the worshipping congregation and visitors alike that Jesus came “to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance” (Luke 5, 32). They will also bring to mind the true saying of Saint Paul, worthy of all to be received: “That Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Timothy 1, 15) as we are instructed during the Service of Holy Communion according to the Book of Common Prayer. From the material that has been presented to me, it would appear that the church are alive to the need both to ensure that there is appropriate diversity amongst the presenters of materials which are to be displayed within the church, and to recognise the vital contributions made to the abolition of the vile trade in human flesh by African and other global majority heritage writers and abolitionists, women and working class reformers rather than simply focusing upon the work of prominent, white, upper and middle class male abolitionists like John Newton and William Wilberforce.’

In an era of cancellation, how has this legacy of a former slave-trader survived? It was an act of redemption but its lasting impact has been helped considerably by other creative acts of genius through the ages. John Newton’s eighteenth century words were blessed fifty years later by the American William Walker who set Amazing Grace in the 1830s to variations on a folk tune known as New Britain, and who popularised this version through his entrepreneurial and religious vocation of selling hymnals. Amazing Grace was revived in popular culture in the second half of the twentieth century. In 2015, it was used to great effect by President Barack Obama in his eulogy for Reverend Clem Pinckney, one of the Black Christians murdered in their own church in Charleston, South Carolina, by a white gunman they had welcomed into their worshipping community. Just looking at the point where the President began to sing, on YouTube, is graceful enough but it is worth watching or listening to the whole eulogy to appreciate the beautiful way in which President Obama introduced grace earlier in his oration and, especially, around the assumption that the murderer would have had about how his victims’ relatives, friends and church community would react, where President Obama made this unattributed allusion to another insight from Olney, this time by Newton’s friend, the poet William Cowper,

‘Oh, but God works in mysterious ways’

lightly paraphrasing the opening line of Cowper’s 1773 hymn,

‘God moves in a mysterious way’.

Instead of nursing a grievance, the community’s reaction was a measured, forgiving kind of grieving, an amazing grace, to which the President added beyond measure. The congregation is electrified by this phrase 16 minutes into the eulogy. Then President Obama begins to talk about grace. He gives a moving reason why sometimes a symbol should be removed, talking about how amazing it would be for the state of South Carolina to take down the Confederate flag in recognition that slavery was wrong. He links this back to God’s grace and faces squarely political controversies around race discrimination in employment and around gun laws. This eulogy is one of the greatest of contributions to the public square. It was only after 35 minutes that President Obama began to sing Amazing Grace.

On this 250th anniversary, then, it is timely to reflect on how we add to legacies and how they are linked. For example, I think it mattered that Newton lived here in Olney, with Cowper and all those oppressed in the lace industry and other disadvantaged circumstances, just as it mattered that Temple, Beveridge and Tawney lived in Toynbee Hall, in the midst of poverty, after their privileged time together as students. Newton and Cowper tried to help the poorest of their neighbours but also learned from them. They exchanged stories of Cowper’s life-threatening mental health issues and of Newton’s life-threatening journeys, including his shipwreck off the northern coast of Ireland.

Listening to Amazing Grace, which might have been directed to him, was thought to be William Cowper’s last experience in church and this hymn might have been his last. I gave the year, 1773, but it was actually in January, indeed in the next day or so after Amazing Grace, before another suicidal episode.

How amazing that, here in this little town of Olney, within hours of each other, Newton wrote the world’s favourite hymn and Cowper wrote the wondrous phrase that is so often echoed, as by President Obama, and which is often assumed to be a Biblical verse, but which was his original expression, about God moving in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform.

I think Cowper might have drawn on the Giant’s Causeway and the storm in which his friend Newton almost died in the imagery of his opening stanza. Unlike Newton’s Amazing Grace, this example of Cowper’s genius has not yet benefited from such a fitting tune. So I wonder if, in death as in life, Newton (whose fame for this itself depends so much on the American Walker’s yoking of his words to the amazing New Britain tune) could come to the aid of his friend, Cowper. Since both hymns are in that 8, 6, 8, 6 syllable-rhythm, and bearing in mind President Obama’s intertwining of the two friends’ words, could ‘God moves in a mysterious way’ be sung to Amazing Grace’s New Britain tune? Might that be one small legacy from the celebrations here today, and around the world, of the 250th anniversary of Amazing Grace?

‘God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform

He plants his footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm.’

Simon Lee lives in Olney and is the Chair of the Trustees of the William Temple Foundation, Professor of Law, Aston University, and Emeritus Professor of Jurisprudence, Queen’s University Belfast

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this