In the second part of their debate about the church’s response to racial justice in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement, Professor Simon Lee (SL) and Dr Sanjee Perera (SP) analyse the concept of White privilege.

SL: What did you mean by ‘privilege’, Sanjee, when you rounded off your list of reasons why we might see #BlackLivesMatter differently with, ‘dare I say, privilege’?

SP: So perhaps an important part of this discourse should be about defining terms. The term ‘privilege’ comes from an expansion of the model of social privilege. In the 1980s, Peggy McIntosh started to unpack some of the ideas of turn of the century thinkers on race and gender, approaching culture and socialisation as an insidious, subliminal form of power. Of course, since then, the nomenclature of White privilege has developed into a more nuanced and complex paradigm. Often, when people debate privilege, they are debating at cross purposes, and discussing entirely different issues.

Professor Anthony Reddie describes this privilege by phenotype as underpinned by a theology of election and English exceptionalism. He suggests it is ‘the advantage of being able to walk into a room and not be defined or stereotyped by a set of ideas and concepts that automatically mark you out as being inferior’ by virtue of colour. ‘It is the privilege of not having to think about one’s identity as it is presented to the world’ (Reddie, Theologising Brexit, p. 17).

In psychology and the social sciences, this model of White privilege contends that Euro-centred or Euro-endowed societies create monological definitions of ethno-racial identification based on colour and phenotype. This means that the sociocultural standards, rules, guidelines and foundations of these societies make ‘Whiteness’ the norm, and everything else is defined according to how it differs from this norm. No effort is invested in understanding the diverse breadth of people of colour. What this means in practice is that a BAME person’s phenotype leads to their identity operating on a deficit model. (Though the term BAME is itself a product of the aforementioned phenomenon and is deeply problematic.) Everything from their qualifications, experience and expertise to their innate characteristics are problematised in a way that they would not be, if they were White. Because primary visual processing is usually the most dominant framing in human cognitive processing, second only to auditory and kinaesthetic information, phenotype becomes a rather powerful currency in socialisation.

SL: You seem to be endorsing the strain in this public debate which treats any human individual as either privileged or not. That’s binary whereas the general thrust of contemporary thinking in other spheres of life is to recognise the fluidity of our identities. Indeed, even Peggy McIntosh, who is mentioned positively by you and is generally credited with having led to this focus on ‘White privilege’, explained her views in 2014 in this nuanced way:

‘But what I believe is that everybody has a combination of unearned advantage and unearned disadvantage in life. Whiteness is just one of the many variables that one can look at, starting with, for example, one’s place in the birth order, or your body type, or your athletic abilities, or your relationship to written and spoken words, or your parents’ places of origin, or your parents’ relationship to education and to English, or what is projected onto your religious or ethnic background. We’re all put ahead and behind by the circumstances of our birth. We all have a combination of both. And it changes minute by minute, depending on where we are, who we’re seeing, or what we’re required to do.’

SP: Of course. Privilege in a particular socio-cultural currency, be it racial appearance, sex, gender, ability or class, doesn’t make you invulnerable or unlikely that other intersectional characteristics are subjected to the deficit model. A White woman may not have to experience the same ignominies that a Black woman might on the grounds of ethno-racial identification, but her gender may make her subject to similar losses of privilege. As you said earlier, this is a more complex, fluid and nuanced reality than Twitter rhetoric might suggest. And it is not an equi-distant, points-based system where one dominant trait might cancel out another; there is no algorithm that might sum up one’s ‘privilege’. Power is an extraordinarily complex trait, based on an ecology of a myriad qualitative whims.

SL: I would like to think that we could agree on duty, if not on privilege. I regard us as under a duty to use our talents, such as they are, to the full, to strive to make a difference, and especially to promote social justice by supporting and encouraging the inclusion of those less privileged than ourselves. The fact that William Temple was one of the most privileged white men ever did not stop him from coining the term ‘welfare state’ and helping to make it happen. He was not responsible for his privilege. He was responsible for using the opportunities he had to promote the common good. He is not defined by his whiteness or his privilege. Nor, for that matter, is he defined by his age. He was ahead of his time.

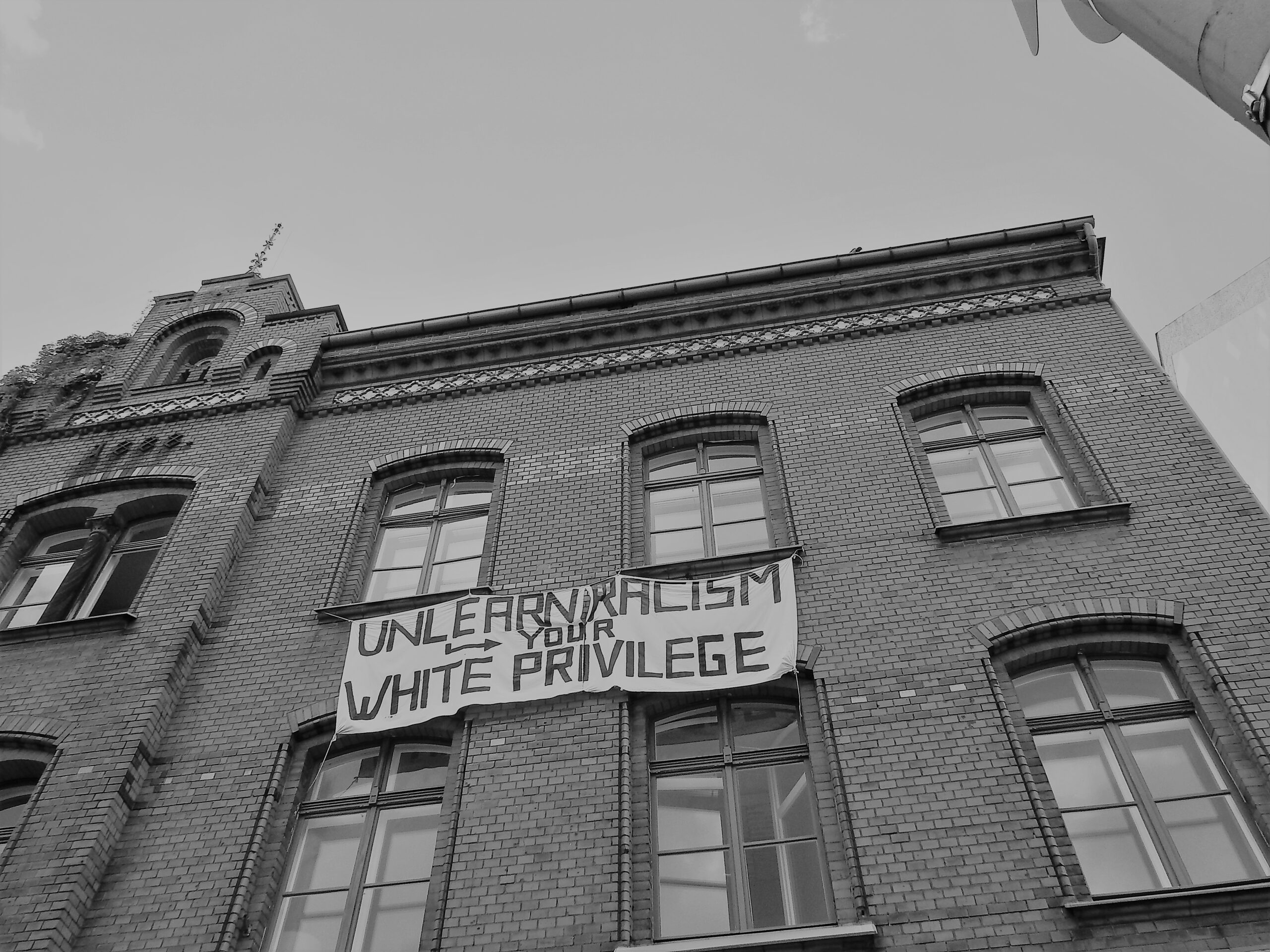

Image: “Unlearn racism, unlearn your white privilege I” by aesthetics of crisis is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

More blogs on religion and public life…

Review of ‘Race, Space and Multiculturalism in Northern England’ by Shamim Miah, Pete Sanderson and Paul Thomas by Greg Smith

Is the climate really beyond politics? by Matthew Stemp

TikTok, Pastoral Care and Lockdown Britain by Kenneth Wilkinson-Roberts

Behind the mask: uncovering symbols of hope in uncertain times by Matthew Barber-Rowell

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this