Gill Reeve wonders whether young adults today constitute a ‘sacrificed generation’. She suggests standing in solidarity with young people and turns to the example of Bishop James Jones for hope.

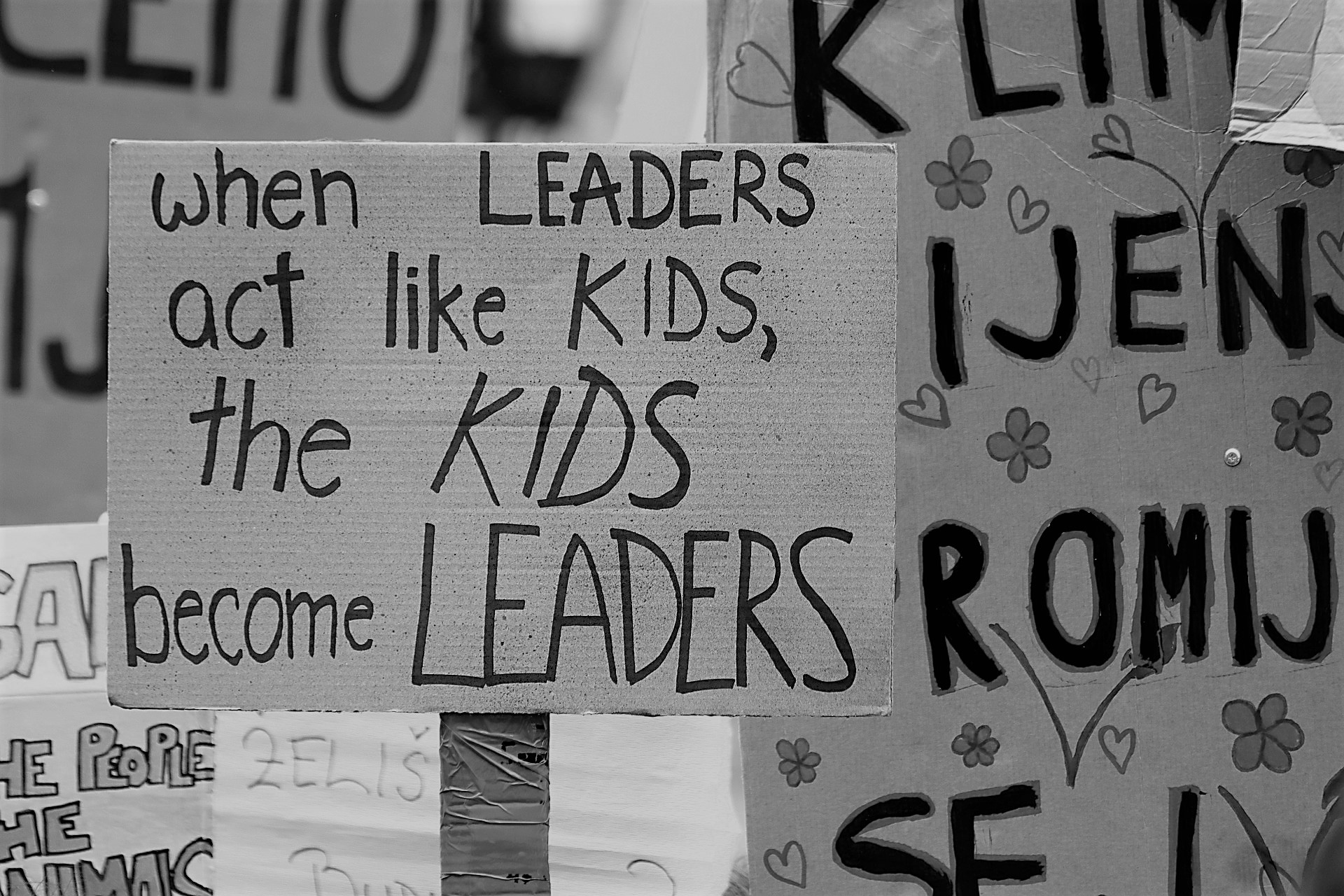

In some recent interviews with young adults in Europe there were some moving testimonies about the profound anxiety that many of them have experienced during the last 15 months and the huge effect the pandemic has had on their futures, mental wellbeing, education, and job prospects. One young adult interviewed describes himself as part of the ‘sacrificed generation’.

The interviews resonated with what I have heard as a chaplain in higher education over recent months. Many of the young adults I have spoken to feel that they have been let down by the government and have largely been forgotten by them. Even before the pandemic, these young adults had many more worries and responsibilities than I ever had in my late teens and early twenties.

As an Anglican chaplain I find myself searching in my own faith tradition for inspiration on how to stand with, and indeed fight alongside, this ‘sacrificed generation’, many of whom are passionate about social and ecological justice. But current Anglican theology seems to fall short when it comes to issues of ecology or justice. Having the environment as just one of the five marks of mission feels a bit like sitting on a sinking ship and reviewing your schedule to see if you have the time to start bailing! It gives the false impression that the social and the ecological are separate entities when they are inextricably bound together.

Someone I interviewed as part of my research into socio-ecological transformation said that they had recently asked a group of Anglicans: ‘Can we change our language? You know, the Roman Catholics talk about ‘Our Common Home’, which is better than talking about THE environment […] we are all in the environment, we are the environment—social cohesion, ecological care, it’s not different.’ Language matters because it shapes our conceptual thinking and informs our action, or lack of action.

Eco-church has certainly been a helpful tool for waking the church up to the ecological crisis, but there is also a danger that it could end up as an introspective response that is too focussed on meeting the church’s own needs. The urgency of the ecological crisis requires a far more holistic framework that emphasises partnership and working with others towards socio-ecological sustainability and justice. For inspiration in this, the church would do well to look to young adults themselves, who are finding ways to form alliances and partnerships that speak together and fight together on the big issues facing our world. Such collaborations are challenging because to fully embrace them we need to relinquish our own plans for the greater good, to let go of the need for recognition of our own achievements, and to listen and learn from others in humility. It is a demanding journey.

So where might I look, within my own tradition of the Anglican church, to help me as a chaplain in my work with young adults? I am inspired by the example of Bishop James Jones who spent much of his ministry engaged in fights for justice, including as chair of the Hillsborough Independent Panel, chair of New Deals for Communities for Liverpool, and leading the Gosport Independent Panel related to hospital care. In an interview in 2017 he states that chairing the Hillsborough Independent Panel ‘became the climax of my time as Bishop of Liverpool. It wove together the three foundational values of my ministry—compassion, truth and justice’. In the late 1990s Bishop James visited schools in Liverpool to listen to what young people were most concerned about, and their overwhelming response was ‘the environment’ (Jones, Jesus and the Earth, 2003). He responded by spending a three-month sabbatical learning more about ecology, reflecting theologically on the care of creation, and gaining wisdom from people from other faiths. Returning to Liverpool he set up the Eden Project (now Faiths4Change) as a multi-faith initiative that aimed to bring communities and faith groups together to work on environmental projects.

What can we to learn from Bishop James about how to stand with young adults in the face of the immense challenges and worries that they face? We must start by listening and learning from young people and allowing that encounter to challenge us and shape our actions. If we are brave enough to fully embrace this, then these experiences will undoubtedly broaden our mindset and enrich and expand our theological thinking. But if we are to stand with this ‘sacrificed generation’ and struggle for a fairer and more just world, then as individuals and as the church we will need to set aside our own needs for security, significance, and growth. We will need new social and ecological values beyond those of the neoliberal metric that has so dominated our worldview in the West.

Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel believes that ‘growthism’ prevents us from thinking about the really vital questions, and he suggests that the way out of this is to embrace degrowth and the decolonising not just of lands and peoples but also of our minds. We need, he says, ‘a new way of thinking about our relationship with the living world’ (Hickel, Less is More, 2020, p. 289). Hickel warns us that: ‘We are in a trance. We slog on mindlessly unaware of what we’re doing, unaware of what we are sacrificing […] who we are sacrificing’ (Hickel, Less is More, 2020, p. 291).

Bishop James speaks of ‘a moral and theological imperative to encourage an embracing of environmental justice’ (Jones, Jesus and the Earth, 2003). And it is within this framework of justice that I believe the Anglican tradition best encourages me to stand with young adults today in their struggles to build a sustainable world and a more hopeful future.

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this