In the second instalment of our series written by members of the Faith & Flourishing Neighbourhoods Network Simon Foster finds himself treading a fine line between creating community and destroying it.

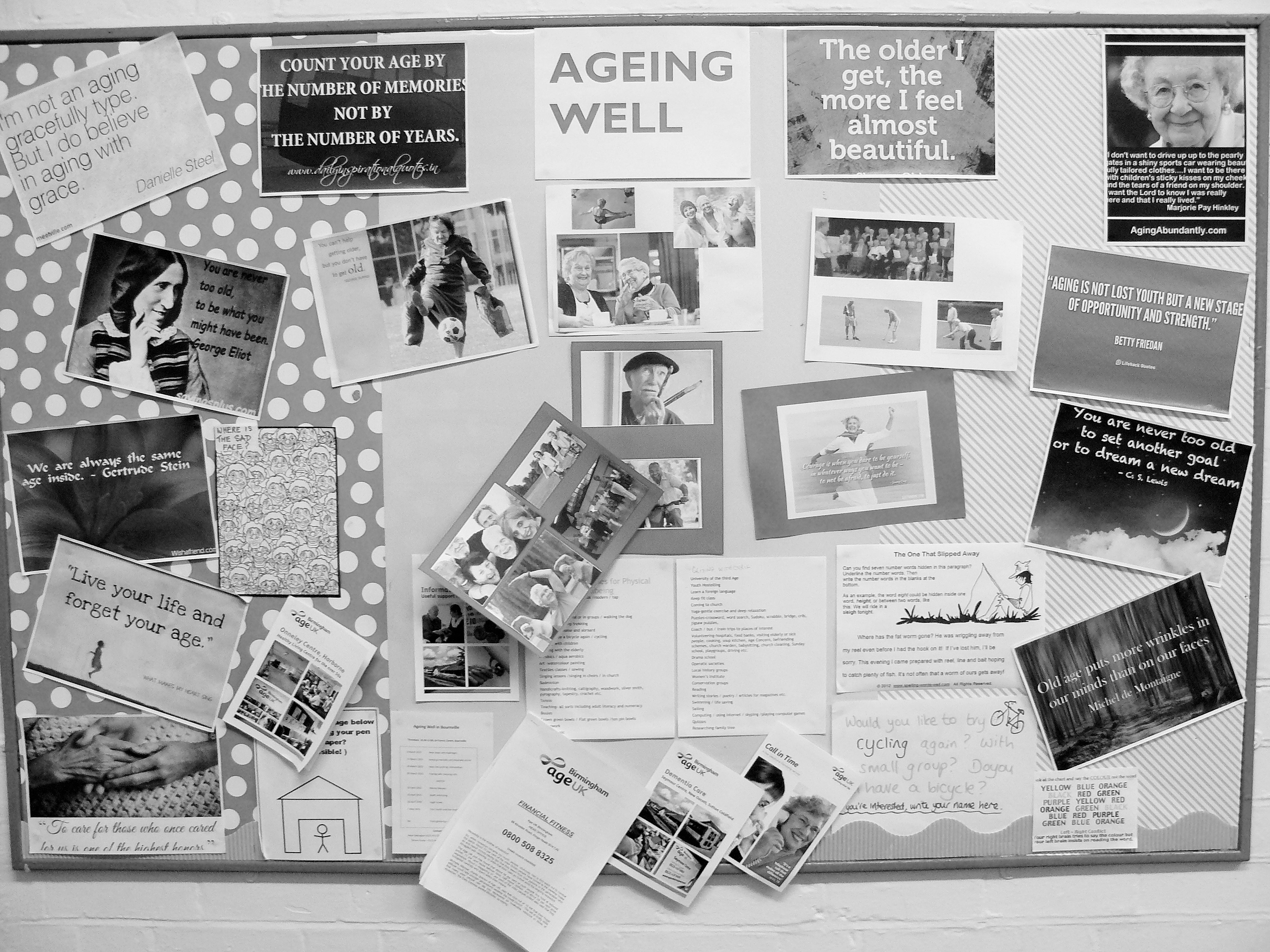

As a social care trainer I’m asked to run all kinds of courses with all kinds of people. So, when I was recently approached to lead a course provisionally called ‘Ageing Well in Bournville’, I automatically said ‘yes’.

Freelancing is a precarious life; accordingly, as a freelancer I always say ‘yes’ to an offer of work. Only then do I stop to think what I have done. When I finally finished congratulating myself on a bit of income, I realised that I had just committed myself to telling a group of eighteen older people how to be older people. I’m 45 years old: not exactly an expert by experience.

That prompted me to reflect what mistakes I might have made in accepting the assignment. I make a lot of mistakes, so in fact it’s a thought process I’ve become quite comfortable with. I reckoned on three. I normally try to confess ten shortcomings at the end of each day, so in one sense, I had really got quite good value from this one action.

My sins, then, were as follows:

- Disempowerment: by leading this course, I would be implying to people that they needed expert knowledge in order to grow in age, and that they weren’t capable of working things out for themselves.

- Hypocrisy: I would be suggesting people be part of a community, yet doing little or nothing to help that to happen. Courses may make people more confident and competent, but despite the buzz of the moment, the typical course doesn’t form lasting community.

- Professionalization: I would be creating dependency. Even if the course was a success, the model would be set in concrete: the community would now have to get funding for a trainer every time they wanted to run it.

Disempowerment; hypocrisy; professionalization. Not the seven deadly sins, perhaps, but damaging enough. I found myself on the brink of replicating the insidious ways of the modern world, which so often fractures community even as it tries to build it.

A better way?

The only problem with facing up to your shortcomings is that eventually you start having to do something about them. I’m no good at that either, but I have learnt that other people are usually gracious. With the help of the Vicar of Bournville, who’d originally approached me, we came up with a better model. A model that, instead of freezing community in its tracks, had some chance of growing it.

This is what we did:

- We recruited a team of five members of his church who were interested and willing to journey with us. They were people who shared concern for the ageing population of which they were part;

- We shared with that team our vision for this course, and I told them that, while I would do as much as was needed, we’d like them to be fully involved. Fully involved, as in, doing everything possible;

- We involved them in all the decision-making around the course: recruiting participants, choosing and utilising the venue; structuring, planning and delivering the course; and reviewing each session afterwards.

The course, which was based on research with older people in the parish, covered challenging areas:

- ‘New and Existing Relationships’

- ‘Facing New Challenges’

- ‘Health and Health Services’

- ‘Feeling and Keeping Safe’

Together, as a co-leader team of 7, we made sure that each session was interesting and interactive. The course had small group conversations from the outset, because with a team of seven, there were co-leaders at every table to facilitate group discussions and keep an eye on any pastoral concerns.

As commissioned trainer, I was present throughout, though rarely presented. The one role that did fall to me was to provide the session plans for each day. Many of the exercises worked, but some did not. The failures were valuable. The co-leaders spent much time contrasting successful and unsuccessful exercises, and in doing so gained still more ownership over the course.

Many of the eighteen or so participants came to us through parish church connections, but not all. The whole group generated an affirming and supportive atmosphere throughout. Some remarked that they enjoyed watching the co-leaders, whom they knew, learning new skills and confidence.

Did we succeed in building community? I hope so: we carried out all the usual post-session evaluations, which gave rich and positive feedback, but actions speak louder than words. Perhaps the test will come when we attempt to run this course again. Will those who attended recommend it to their friends? Will some work hard to attend the sessions they missed? Will some join the co-leader team?

As for me – I have learnt once more that the more mistakes I make, the better it is for the community around me.

Simon Foster is a freelancer interested in how to nourish community in practice. His work explores the borderlands of community, social and health care, and faith.

Read the first blog post from the series: What Does My Community Ask of Me? by Will Jones.

More from our bloggers:

Is Capitalism a Religion, or Religion Another Form of Capitalism?

by John Reader

How the Rich Make More Money, And the Church’s Obligation to Respond

by Eve Poole

Pope Francis & Naomi Klein: Celebrity Brand or Postsecular Tipping Point?

by Chris Baker

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this