Matt Stemp proposes that anger might be more fruitful than frustration as a galvanising emotion for climate protest.

One of Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) rally cries in its early days as a social movement organisation was ‘love and rage’. Love is certainly difficult to miss in XR’s emotional culture. At its 2019 protests, the climate activists would often read what became known as the ‘Solemn Intention Statement’, which invited everyone present to ‘recall our love for all humanity’ and ‘remember our love for this beautiful planet’. It was this universalism of love and compassion that, in part, has made XR an attractive and welcoming space for faith-based activists. As one member of XR Buddhists once said to me: ‘What could be more Buddhist than that!?’. XR members habitually sign off their emails with ‘L&R!’. But in my interviews with (predominantly white) activists, anger is one of the least frequently mentioned emotions. Far more common, when asked about their feelings about climate change, are fear, anxiety and despair about the future (especially for younger activists and parents), sadness at the state of the natural world, and guilt at their own complicity with inaction. XR groups sometimes meet in ‘grief circles’ and ‘empathy circles’, but I have yet to find activists gathered in the name of anger.

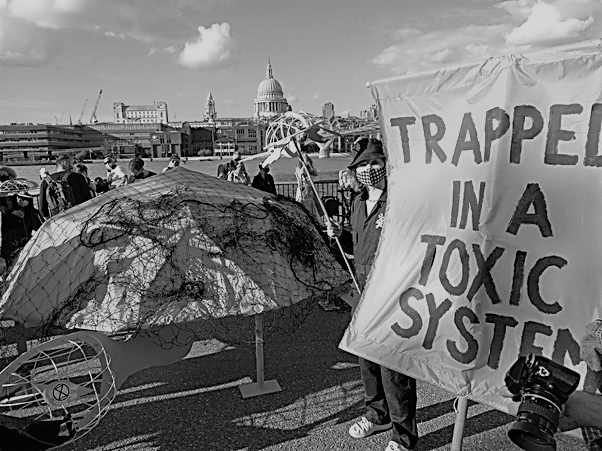

Instead of outrage, XR activists are far more likely to talk about frustration (often without using the word). They are frustrated with the government, with corporations, with churches, even with the apparent apathy of their colleagues and friends, struggling against the relentless and immoral continuity of the socio-political status quo. They are perennially dismayed that ‘the world’ continues to ‘binge’ on oil and gas, as one recent eye-opening Twitter thread by XR Cambridge puts it, listing all the new ventures for the extraction of fossil fuels that continue to be funded by countries allegedly committed to reducing carbon emissions. Underneath all of this is activists’ sense that their agency is frustrated by an undemocratic society that does not recognise the voices of its citizens, requiring a politically liberal response of civil disobedience as a last resort.

Emotions are slippery things—if they are things at all. In line with its Latin roots (emovere, to move), it is common to refer to ‘emotion’ as something ‘inside’ people that moves them to act. Historically, protestors have been portrayed as irrational, moved not by reason but by passion, and that tradition continues in the labelling of anti-racism demonstrations as ‘riots’. But, as Sara Ahmed argues in her classic book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, emotions are not psychological states, even if late capitalist culture has taught us to experience them as the private feelings of some innermost self. Rather, emotions are social and cultural practices that create the very distinction between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’.

Conceived in this way, frustration is an emotional practice that constructs the difference between an all-powerful external world and a disempowered internal self. In XR, this distinction is often morally (or sacrally) charged by language of pollution and purity, describing how a generalised ‘toxic system’ is poisoning the planet for future generations and fellow species. In terms of inside and outside, frustration is therefore closely related to despair and guilt: in despair, the world pollutes the self, while in guilt, the self pollutes the world. Indeed, James Jasper, in his comprehensive volume The Emotions of Protest, describes frustration as a ‘desperate mood’ that in its most productive form creates a ‘nothing-to-lose effect’—in XR’s case, direct action to protect ‘all we hold dear’.

By contrast, Ahmed argues in relation to feminist anger that anger ‘moves us by moving us outwards: while it creates an object [e.g., patriarchy], it also is not simply directed against an object, but becomes a response to the world, as such.’ Ahmed draws on Audre Lorde’s essential essay, Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism, to argue for the necessity of anger as the foundation for a feminist and anti-racist politics, while remaining cautious about when and how anger should be performed. Importantly, Lorde’s essay distinguishes between hatred and anger: ‘Hatred is the fury of those who do not share our goals, and its object is death and destruction. Anger is a grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change.’ If frustration partners too easily with despair, then, for Ahmed, anger belongs with hope: ‘Hope is crucial to the act of protest: hope is what allows us to feel that what angers us is not inevitable, even if transformation can sometimes feel impossible.’

It is always a dangerous move to make a normative claim about emotions. But I have been convicted and inspired by attending the recent protests in London against police brutality, the suppression of protest and institutional racism, to consider why my own activism with XR has been shaped more by frustration than by anger. The answer, I have concluded, at least in my own case, is very simple: that the emotional regime of the ‘toxic system’ (let us call it what it is: white and male supremacy) serves my interests rather too comfortably. Deborah Gould, in her magisterial work Moving Politicson ACT UP’s activism around AIDS in the 1990s, states that: ‘Feeling anger is sometimes an achievement, and not always easily accomplished.’ For me, and I suggest for my fellow white activists too, anger is a practice we need to do the hard work of (re-)learning for the cause of climate justice. Then the slogan ‘Love and Rage’ might return to us with fresh meaning and purpose, in greater solidarity with those whose lives are oppressed and destroyed by the fossil fuel industry and the capitalist interests it serves.

Images by Matt Stemp.

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this