Maria Power praises the new edited volume ‘Coming Home’ for its much-needed theological reflections on housing and homelessness.

Over the past 18 months, the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdowns have taught us just how important our homes are. For those of us who live in cities, our proximity to our neighbours, along with our constant presence at home, has led us to get to know them well. When the first lockdown began in March 2020, we were thrown into a crisis situation with people that we might previously have been on ‘nodding terms’ with. Whilst this has been trying in some circumstances; in others it has been a blessing, and relationships and friendships have formed that have created a new sense of community and a greater sense of place. Through the experience of the pandemic, we’ve come to realise that our homes aren’t just boxes that we retreat to at the end of a long day at work, but rather part of a wider whole. Home is now somewhere we work, educate our children, spend our leisure time, socialise, eat, and rest. More importantly, they are an essential element of our identity—an identity which is not just formed by the physical presence of the building and the way we choose to live in it, but the relationships we form because of it and the ways in which we use it as a base from which to go out into the wider world and build community.

The issue of housing and home, then, has a fundamental impact on our wellbeing. If all is well in our homes, we can flourish. If not, then everything becomes a struggle. Just having an address allows you to do so many things: securing employment, accessing healthcare and educational opportunities, opening a bank account, applying for social welfare, and using the local leisure centre and library, for instance. Homelessness (be it couch surfing, living in your car, or sleeping rough) is much more than the indignity and trauma of not having a place to eat and sleep; it cuts you off from society.

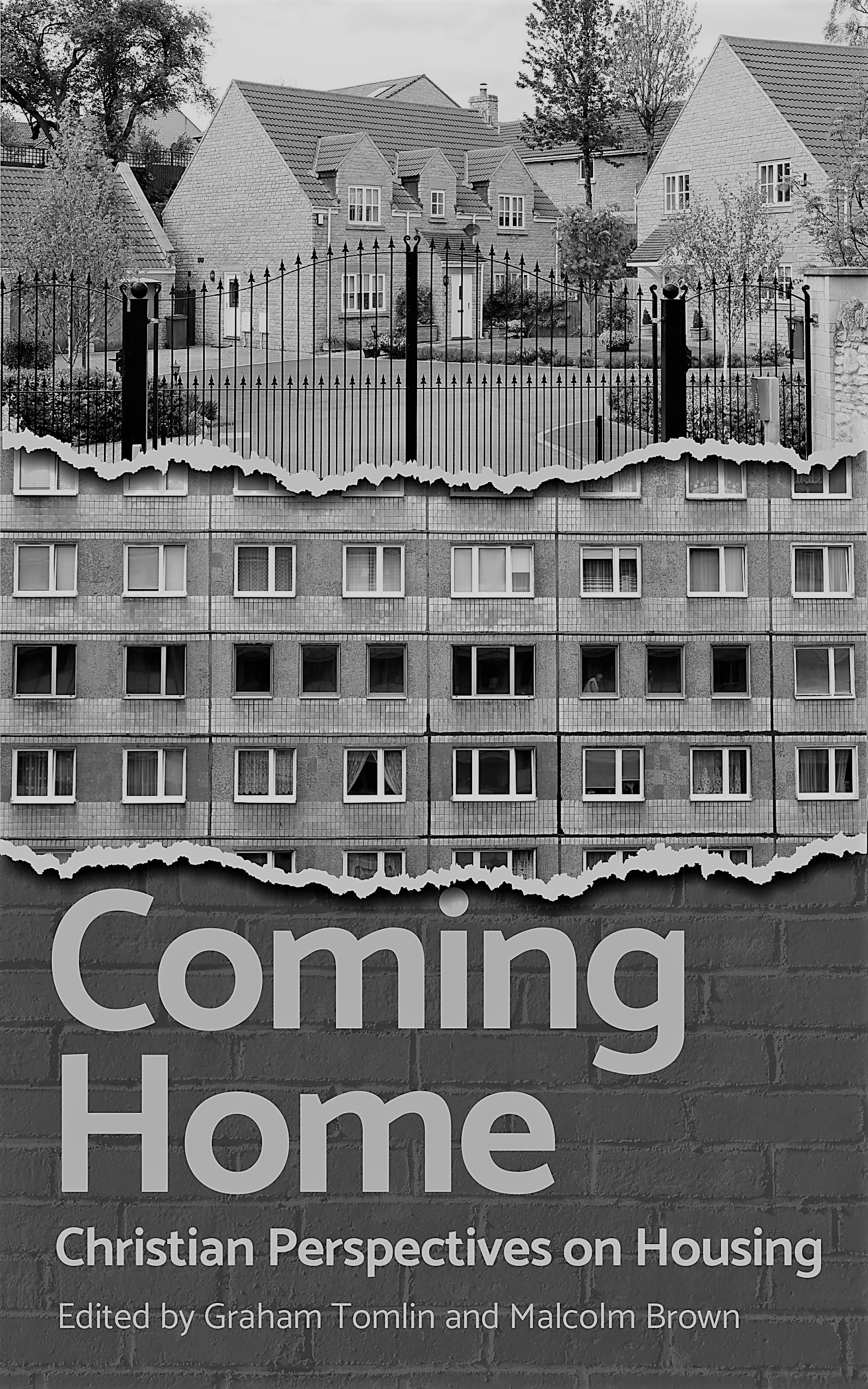

Given the importance of housing and home to our sense of well-being and identity, I have always been perplexed by the lack of theological reflection on the issue. With the notable exception of the work of Tim Gorringe on the built environment, those of us seeking to understand the role that housing and home plays in human dignity and flourishing have little to rely on. That is why the work of Malcolm Brown and Graham Tomlin in editing Coming Home: Christian Perspectives on Housing should be so gratefully received by academics and practitioners alike.

This collection contains ten essays written by contributors who include academics, chaplains, PhD students, and those who have made the theme of housing a fundamental part of their ordained ministry. It ‘deliberately combines contributions from established and well-known theologians and practitioners, and some younger emerging voices.’ (p. xv) Coming Home is one of the outcomes of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Housing, Church and Community which was established in 2019 following the publication of Welby’s Reimagining Britain in 2018. The goal of this commission and the subsequent publication is worth quoting fully:

The challenge was to think clearly about what a Christian approach to housing might look like. Might it be possible that the light shed by Jesus Christ, the light of the world, into the dark places of housing injustice and poverty, could help us to reimagine what good housing looks like and shine new light on a crisis that has defeated the best efforts of many governments and specialists over the years? Our hope was that a Christian view on housing would inform our further proposals to government, the wider Church and diocese and to the local church. (p. xvi)

This collection of essays, therefore, has laudably high aims. And, for the most part, it achieves those aims. Between them, the ten essays included in this book begin some much-needed theological reflection on the issue of housing and home–though they represent a starting point rather than an end point in the discussion. Two essays in particular stand out.

The first, by theologian Tim Gorringe, offers ‘Theological Priorities for Housing’, which ties the issue at hand to the very foundation of faith—the Bible. In this essay, he starts by showing us how crucial the issue of home and the built environment is to Christian faith. The fundamental importance of home therefore has implications for the built environment. And he lists six theological priorities for the building of houses: sustainability, justice, community, empowerment, beauty, and life. The most striking argument he makes is also the most obvious, but it bears repetition nonetheless:

We have to ask what vision of society we want our buildings to embody, and what materials we ought to use. The question “how should we build?” implies a vision of society as a whole. Human ecology is part of planetary ecology. This means that questions about building cannot be divorced from questions of culture, politics and spirituality. (p. 20)

The key here is the issue of imagination and the creation of alternative possible futures, not only for ourselves as individuals but also for society as a whole. Such work cannot be left to policymakers alone; Christians, too, ought to become more involved in shaping society. Only through such involvement can the kingdom become a reality.

The second essay, by Niamh Colbrook, considers ‘The Integrity of Creatureliness: Materiality, Flourishing, and Housing’. As a PhD student, Colbrook is one of the emerging voices referred to by Brown and Tomlin in their introduction. Her essay is a model of good public theology, offering a blend of insights from the social sciences with theological reflection through the lens of creaturely integrity. She concludes with suggestions to help Christians discern their response to the housing crisis. Her argument relating housing to flourishing is particularly helpful:

The housing crisis, then, brings us face-to-face with the systematic inequalities that impede flourishing both in the short- and long-term, and their emergence in and through our relationship with our material environments. (p. 110)

This is an accessible and inspiring collection of essays, which encourages us to take responsibility for developing solutions to the housing crisis. I hope that it is widely read and considered, both by policymakers and by local parish communities.

Dr Maria Power is a Senior Research Fellow in Human Dignity at the Las Casas Institute for Social Justice, Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford. She is a Senior Research Fellow at the William Temple Foundation. Maria is currently researching the role that housing and urban regeneration can play in peacebuilding in Northern Ireland.

Discuss this