Last week on twitter, Humanists UK, quoting their Vice President, Professor Alice Roberts argued, ‘We really don’t need more faith schools in this country. I wish the government would prioritise inclusive schools, rather than using taxpayer’s money to fund the Church of England’s indoctrination programme.’ Professor Roberts voices concerns of uncritical pedagogy she believes is found in Church of England schools, and the way the curriculum frames Science, History, Faith, and Theology. And as a Bill to disestablish the Church of England had its first reading, Humanists UK are not the only voice to raise concerns of this kind.

The Church has had a historically tumultuous relationship with science, which has both shaped the course of science and the doctrines and theology of the Church. The church was undoubtedly a patron of the sciences, believing that the gift of reason was a divine providence and an instrument of theology, championing science, believing it would confirm Church doctrine. But when scientific findings did not match the Church’s doctrinal or even political stands, this relationship soured into inquisition and condemnation.

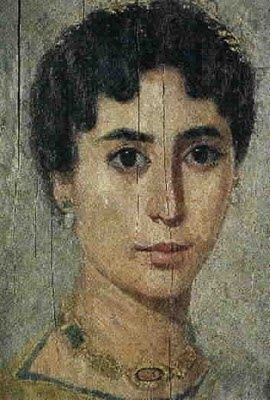

The early Church’s most infamous episode perhaps begins with Hypatia of Alexandria, the 4th century mathematician who was brutally attacked on her way home, dragged out of her carriage and murdered by a Christian mob. Hypatia was reviled for her influence on leading Christians of the time. But the attack on her reputation and the attempts to discredit her were incited by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria and his allies, mostly due to her relationship with Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria, who they feared ceased to attend Christian meetings as a result. Nevertheless, Hypatia’s impact on the political struggles of the Church has been dramatized, discussed and diagnosed at length, but more importantly her teaching schooled at least one bishop of the early Church and influenced countless others. This was neither the first nor last struggle of the early church with science.

Almost a millennium later, Copernicus’s heliocentrism was the scientific paradigm of the day which seemed to undermine doctrine. Despite early toleration and even goodwill from Pope Clement VII, in 1616, the Roman Church issued a prohibition against teaching heliocentrism. This led to the persecution of Galileo who continued the work, and a papal Bill prohibiting heliocentric works. Nearly two centuries later, the weight of scientific evidence made the Church’s position indefensible, and the College of Cardinals finally revoked this prohibition. But it wasn’t until 1992, that Pope John Paul II formally conceded to Heliocentrism, and another 8 years before an apology (rehabilitation).

More recently there is John Habgood. Famously he arrived at Cambridge with a militant atheism and made ‘outrageous remarks about religious beliefs and the intellectual and moral qualities of those who held them’, only to convert, be ordained, and eventually become the Archbishop of York. Alister McGrath, in his deconstruction of Habgood’s legacy argues that, like Archbishop Frederick Temple (1896–1902) and Bishop Ian Ramsey (1966–72), Habgood ’acted as an institutional and professional bridge between the intellectual worlds of science and theology, and the church and a scientific culture’. However, with the exception of the ECLAS project, funded by the Templeton Fund, I would see the Church of England’s engagement with science is sporadic at best, with lamentable levels of research available on the impact of scientific advancement on Church doctrine, vision, engagement, and growth.

Listening to the Living in Love and Faith General Synod debate about same-sex relationships and scriptural interpretation relating to the nature of marriage, I was struck by the often-literal readings of scripture. And while some eminent scientists had earlier been involved in the biology and social scientist sub-group, their discussions were not a significant part of the synod’s discourse. The decline in Church attendance is often the throw-away evidence that almost every synod debate alludes to, with conservative members claiming that liberal and progressive churches are dying. And yet no recent discussion at synod has considered the significance of the impact of science on the church. The cognitive dissonance caused by moderating the disparate realities of a literal and fundamentalist reading of scripture in determining significant issues of doctrine has undoubtedly had an impact on this alleged Christian nation’s psyche in a post-Christian era.

In the 21st Century, many have responded to this dissonance by divorcing themselves from the religious establishment, leading to seeming irrevocable church decline. Linda Woodhead claims that the rise of ‘no religion’ in national surveys and census records has been swift in many formerly-Christian liberal democracies, with Britain located as a significant frontrunner. Her research reports that when asked how they make up their minds about difficult decisions, the overwhelming majority of British people, including many who report some religious engagement, say that they consult their own conscience, reason and intuition rather than relying on an external authority. Her research also illustrates that Church decline is often tied to the stark contrast between evolving liberal social attitudes and the prejudice and discrimination associated with established religion.

Believers navigating the dissonance between the advancements of science and technology and our understanding of the historicity of sacred texts, alongside ontology, phylogeny and human evolution, often compartmentalise faith experience and literalist biblical discourse. But compartmentalisation is not a sustainable or a viable coping strategy and often creates disenfranchisement and disassociation which in turn lead to disengagement and decline. My own research assessing cognitive dissonance in faith communities, exploring indicators of identity distress, de-individuation, detachment, disassociation and compartmentalisation in marginalisation experiences in church contexts, finds that these coping strategies are the threshold of church decline.

Too often the Church has responded to science with fear, defensiveness and a self-imposed compartmentalisation and isolation, to its own detriment. The ecclesia, like many scientific bodies, is often a community strangled by wilful dogma, fallible to error, and yet enthralled by the mystery and enigma of the universe. And most significantly we are communities driven by existentialist questions with an appetite for revelation and reason, bewildered by serendipitous logic, design, beauty and grace. Amidst the looming prophecies of the extinction of the Church of England, perhaps it is time to seriously re-engage with science, to be challenged by its questions, to fund its research, to collaborate on its adventurous quests, if not unquestioningly be led by its tenets. This can only better equip us to navigate faith and doctrine, and perhaps even be nourished and course corrected by its findings.

Canon Dr Sanjee Perera is Cognitive psychologist specialising ethno-social identity, moral judgement and decision-making. She is a Honorary Fellow at the Department of Theology & Religion, Durham University.,Associate Fellow, Open University School of Law, Visiting Fellow, Centre for Trust, Peace & Social Relations, Coventry University, Honorary Research Fellow, Theology and Religious Studies, University of Chester, and a Research Fellow at William Temple Foundation.

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this