Tina Hearn turns to William Temple for the principles that must be prioritised in healthcare policymaking if we are to truly ‘build back better’.

‘History may not repeat itself, but it can rhyme’ (Mark Twain).

Before the end of the Second World War, William Temple and aligned proponents argued there was a pressing need to ‘build back better’ in all policy areas, including welfare—a position eventually embraced by all parties. The trope of ‘build back better’ echoes again across the polity today, so, yes, history has rhymed around the broad need for policy reform. However, today, there are also profound dissonances with regard to Temple’s policy principles.

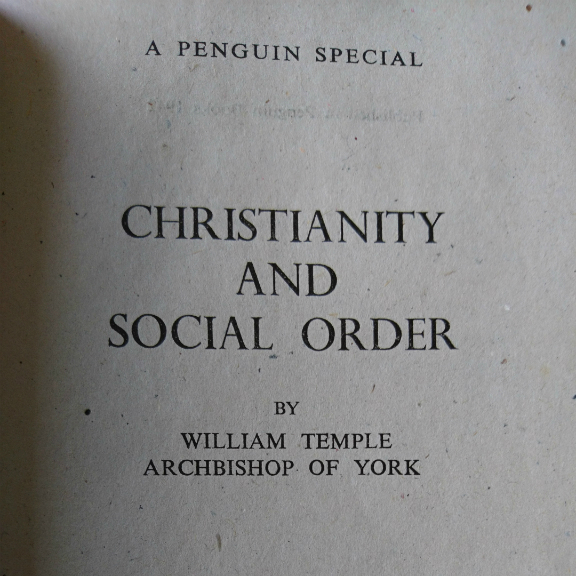

To inform the project of building back better, Temple crafted a series of principles in Christianity and Social Order, as well as in his broader writing. One of Temple’s key principles was the Christian idea of fellowship in the form of democratisation, which he claimed should inform all areas of socioeconomic life. He argued that democracy and its constituent principles—such as representation, responsiveness, and accountability—‘deepens and intensifies personal fellowship’ giving ‘the highest value to the personality and personal relationships of all citizens in the community’ (Church Looks Forward, pp. 142-143). Temple viewed de-democratisation as corrosive of human personality, fellowship, and broader society.

However, many contemporary policy developments are highly dissonant with Temple’s principles. This is evident across a range of contemporary policy developments, which will profoundly shape welfare policy futures, including the Health and Care Bill which has just received its second reading in parliament.

A widespread concern about the Health and Care Bill, is that it embodies a range of de-democratising policy principles and provisions. For example, as the British Medical Association (BMA) has noted, the Bill contains provisions which afford increased powers to the secretary of state, arguing that it is ‘totally wrong for Government to have the power to abolish arm’s length bodies without due scrutiny, approve or reject Integrated Care System (ICS) chairs, or interfere with local decisions’. The BMA has also expressed concerns about the threat of private health providers having a formal seat on ICS boards, the new decision-making bodies, and wielding influence over commissioning decisions. This is already the case in Bath and Somerset where Virgin Care has a seat on the local ICS and is leading on the Integrated Care Record Initiative.

Temple argued that the ‘private sector will inevitably put private sector interests first. If we want to put the public interest first, we must so organise our life that those who are chosen for their concern with and qualification to judge the public interest are in positions of control’ (Church Looks Forward, p. 110)—a view supported by evidence on private provider companies. People who receive care and local communities are also important stakeholders here. However, the Bill has no specific provisions for patient or community representation on the new Health Boards. The Bill thus exhibits tendencies towards amplifying centralisation and sectoral commercial interests rather than democratisation.

The scope for outsourcing health services to the private sector in the Bill, arguably poses further democratic risks and erodes accountability. This is not new: the significant expansion of outsourced health care since the 2012 Lansley Act has created multiple democratic fault lines across the NHS. A lack of transparency, regulation, and accountability around outsourced provision has been widely noted both prior to and during COVID. This is a worrying trend, amplified by the diminution of transparency through repeated appeals by the government to ‘commercial confidentiality’ to justify non-disclosure of a range of procurement and contractual information. There are also concerning indications that there are moves towards reducing the level of regulation still further, with a regulatory review contracted out to KPMG.

The anti-democratic implications of the increase in health service provision exports to private sector providers also needs to be considered alongside the strong anti-democratic tendencies which increasingly prevail across the economy. For example, the representation and participation of labour in discussion and decision making has been significantly eroded. The exercise of monopoly power in the form of the dominance of large corporations has increased. And there has been an increasing number of service contracts issued to companies such as private equity, whose primary drivers are shareholder returns rather than public good—a trend echoed in social care services.

It should be noted that the Health and Care Bill forms just one plank of the government’s proposals to ‘build back better’ for the future. This brief review of some of the provisions of the new Health and Care Bill indicate that the provisions and principles of the Health and Care Bill run counter to, and so undermine, Temple’s appeal to fellowship and democracy. More worrying still, these tendencies are also evident in policy initiatives and proposals to reform further areas of the welfare state, including education, social security, and housing—and indeed extend beyond welfare reform, for example, in the Crime, Policing and Courts Bill and proposals to reform judicial review. Of course, there are different views around what principles should inform any process of ‘building back better’. However, current developments do not sit comfortably with Temple’s principles, nor with a wide range of positions on the political spectrum, including the professed libertarian position of the current administration (for whom, logically, a centralising, controlling state is an anathema).

Much of what could be done to improve health policy such that it rhymes more effectively with Temple’s principles of fellowship and democracy could be achieved through annulling the policy dynamics outlined above. Of course, democratising initiatives could be extended far beyond this: equalities legislation and social purpose provisions could be firmly integrated into procurement processes, prioritising public-interest-oriented service provision; service principles could be developed through deeper and wider consultation; top-down management processes could be replaced with stakeholder management models; and the list could, and should, go on. As Temple presciently noted, without due attention to clear policy principles there is a risk of welfare policies emerging that have strong, centralising, anti-democratic inflections—the direction in which we clearly seem to be heading.

Dedicated to Prof Kailash Chand OBE FRCGP, who died on 26th July 2021.

More blogs on religion and public life

- Faith and Voting: The UK general election 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Labour and Faith – Brave New Reset or Faith-Washing?

by Chris Baker - Lessons for an election year from the Bishop of Unity

by Ian Mayer - Food, hope and love: the local church in a time of crisis?

by Paul Monk - Radical hope in the midst of poverty in the city

by Grace Thomas

Discuss this