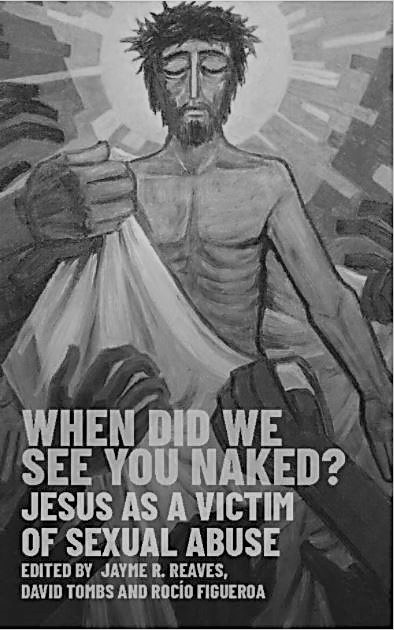

This week’s blog, by Karen O’Donnell, is adapted from her chapter ‘Surviving Trauma at the Foot of the Cross’ in the recently published book ‘When Did We See You Naked? Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse’, edited by Jayme Reaves, David Tombs and Rocío Figueroa. Content warning: sexual abuse.

This blog post comes from a new book that examines Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse. As well as considering Jesus as one who was sexually abused, I am interested in those who witnessed what happened to him from the foot of the cross. The gospel stories never tell us what the impact of witnessing the sexual abuse, humiliation, torture, and eventual death of Jesus was on the small group of family and close friends who gathered at the foot of the cross. Implicitly, these stories point to the resurrection as the thing that makes sense of the horror of the cross. It is likely, however, that those who witnessed Jesus death experienced events that would likely begin to the meet the criteria for a modern diagnosis of trauma. They witness the abuse and death of one to whom they are close. How could they not be impacted by such an experience?

Telling stories is a key element in post-traumatic remaking. The gospel stories are the stories of the early church—stories that give space for flourishing. These stories are born out of collective memory and trauma is embedded in this memory. This cultural memory is not confined to those living in the immediate aftermath of the death of Jesus, but is passed along, with cultural trauma, through lines of religious inheritance.

It is not the case that all Christians are traumatised because we have this traumatic experience in our collective memory. That perspective does no justice to those who experience horrific, complex or ongoing traumatic experiences. But I am highlighting two things: first, the recovery (or uncovering) of the nature of the violence and sexual abuse in the torture that led to Jesus’ death; and second, the impact this had on those who stood at the foot of the cross. What might it mean to take seriously both the possibility of Jesus’ own sexual abuse as part of his crucifixion alongside the possibility that those who witnessed his death were traumatised by the sexual abuse they witnessed?

Uncovering the nature of the violence and sexual abuse that Jesus suffered at the hands of those persecuting him allows a fresh consideration of the cross. This method of torture and crucifixion suffers from the contempt of familiarity. We are so used to hearing the gospel narratives—with all their absences and gaps—and so used to seeing the graceful body of Jesus on the crucifix that the cross has lost some of its power to shock and repulse us. Uncovering the sexual element of Jesus’ abuse and torture helps us to consider the cross with fresh eyes, particularly from the vantage point of a society that is wrestling with experiences of sexual abuse and questions of belief in those who report it. As to the recovery/uncovering of the second point, we should not assume that the group of relatives and close friends were unaffected by the experience of witnessing this torture and abuse as they stood at the foot of the cross.

If we allow these two ideas to impact us in the present day, what might it mean for us as contemporary Christians to witness the violent torture, abuse, and death of Jesus from our perspective at the foot of the cross? We are heirs to a cultural, religious inheritance that bears this traumatic memory within it, and we read, perform and experience this narrative through the biblical texts and the church’s liturgies.

Those who stood at the foot of the cross were witnesses to the humiliation, torture, abuse and murder of Jesus. They were also witnesses to the wider world—their community of disciples in the first instance, but ultimately a much broader scope of witnesses—of what had happened to Jesus. Believing and telling this story had dramatic impact. As a trauma survivor constructs their trauma narrative—a key element to post-traumatic remaking—it must be witnessed and believed by others. In trauma theology, this witnessing community has been much emphasised as a role that the church can play in supporting survivors of trauma. Hearing and believing survivors of trauma—particularly survivors of sexual assault—is a topic subject to much contemporary discussion. Since the explosion of the #MeToo movement in 2017, it has become apparent that sexual abuse, assault, and harassment are endemic in our society. The church is, sadly, no exception.

This Good Friday, take the opportunity to look at the cross with fresh eyes and see not only the brutal death of Jesus, but the impact that his experience has on those who remain at the foot of the cross. What might it mean for the church to be a place where trauma survivors, including those who have experienced sexual abuse, are witnessed to and believed? Where their experiences are not brushed under the carpet but shared in the daylight and grieved? As witness to such trauma, we need to resist rushing to the resurrection of Easter Sunday but instead remain—as the love of God always remains—in the despair and chaos of Good Friday and Holy Saturday.

Dr Karen O’Donnell leads the postgraduate programmes in Christian Spirituality at Sarum College. Her research is focused on the impact trauma has on faith and theology. Her most recent (co-edited) book is Feminist Trauma Theologies: Body, Scripture, and Church in Critical Perspective.

More blogs on religion and public life

- Faith and Voting: The UK general election 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Labour and Faith – Brave New Reset or Faith-Washing?

by Chris Baker - Lessons for an election year from the Bishop of Unity

by Ian Mayer - Food, hope and love: the local church in a time of crisis?

by Paul Monk - Radical hope in the midst of poverty in the city

by Grace Thomas

Discuss this