In this special blog for Eastertide, Stephen Cottrell, Archbishop of York, explains the Church of England’s new vision for the 2020s.

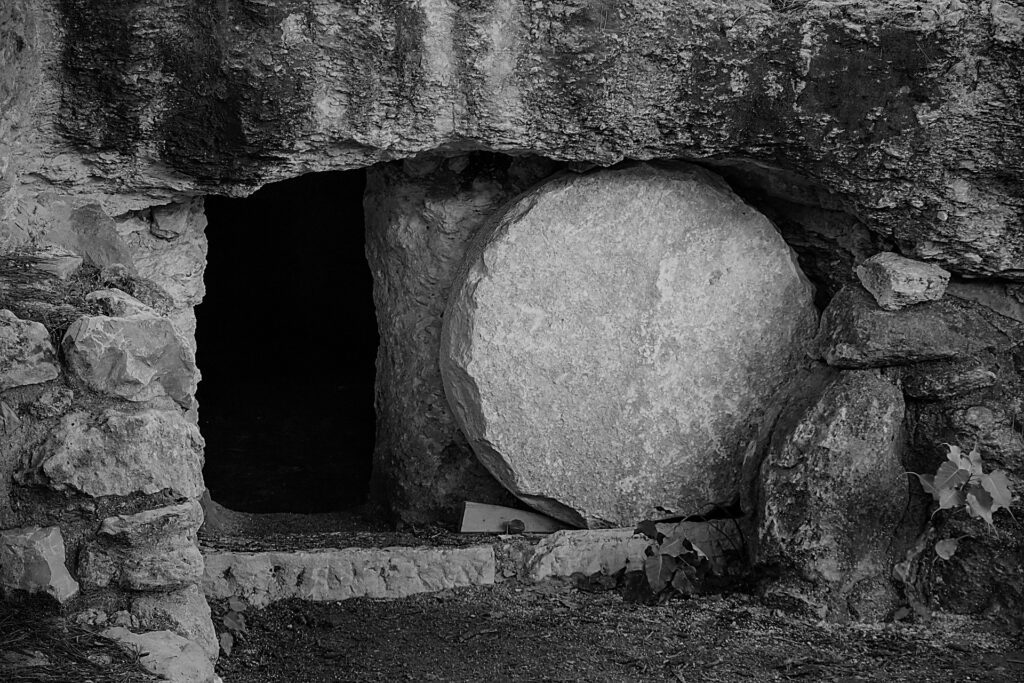

Easter is a time of great hope. It is the season when Christians remember Jesus’ death on the cross, his victory in resurrection, his ascension into heaven and the disciples receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. That gift nearly 2000 years ago is the reason why Christianity continues to this day and why Easter is such an important celebration in the Christian calendar.

It is with this same Easter hope, rooted in the good news of Jesus Christ that the Church of England has embarked on its vision for the 2020s. It was William Temple, when appointed Archbishop of York, who wrote to a friend to say, ‘It is a dreadful responsibility, and that is exactly the reason why one should not refuse’ (letter to F. A. Iremonger, August 1928). Shortly before I was appointed to follow in his footsteps, albeit 91 years later, I had been asked to give some thought to what the Church of England’s vision for the 2020s might look like and, if I am honest, similar words to those of Temple went through my mind.

However, as I embarked on this task, I was clear on two things. This should never be about my vision, but about discerning God’s vision for God’s church in God’s world—and therefore I should not attempt to find it on my own. Over the next 9 months, various groups were gathered together, representing a huge, and usually younger, diversity of voices. After much prayer and discernment a vision emerged which we felt was God’s call on us for this time. Consequently, there is now a clear Vision and Strategy that the governing body of the Church of England and the Diocesan Bishops have agreed—and the whole Church is shifting and aligning to this new narrative.

Except, it isn’t that new. The Church of England’s vocation has always been to proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ afresh in each generation to and with the people of England. In our vision for the 2020s, we speak about this as being a Christ-centred Church, which is about our spiritual and theological renewal, and then a Jesus-Christ-shaped Church, particularly seeing the five marks of mission as signs and markers of what a Jesus-Christ-shaped life might look like. It is therefore a vision of how we are shaped by Christ in order to bring God’s transformation to the world. Three words in particular have risen to the surface: we are called to be a simpler, humbler, and bolder church.

From this, three priorities have emerged, and parishes and dioceses are invited to examine and develop their existing strategies and processes in the light of these ideas.

- To become a church of missionary disciples. In one sense, this is the easiest to understand, re-emphasising that basic call to live out our Christian faith in the whole of life, Sunday to Saturday. Or, as we speak about it in the Church of England, Everyday Faith.

- To be a church where mixed ecology is the norm. This has sometimes been a bit misunderstood. Mixed ecology reflects the nature of Jesus’ humanity and mission. It is contextual, ensuring churches, parishes, and dioceses are forming new congregations with and for newer and ever more diverse communities of people. It is about taking care of the whole ecosystem of the Church and not imagining one size can ever fit all. In the early church, in the book of Acts, we see this mission shaped by the new humanity that is revealed in Christ, made available and empowered by the Spirit. Therefore, mixed ecology is not something new—it is actually a rather old, and well-proven concept. After all, every parish church in our land was formed once. So, mixed ecology doesn’t mean abandoning the parish system or dismantling one way of being the Church in favour of another. It is about how the Church of England will fulfil its historic vocation to be the Church for everyone, by encouraging a mixed ecology of Church through a revitalised parish system. We hope that every person in England will find a pathway into Christian community.

- To be a church that is younger and more diverse. Professor Andrew Walls writes, ‘The Church must be diverse because humanity is diverse, it must be one because Christ is one […] Christ is human, and open to humanity in all its diversity, the fullness of his humanity takes in all its diverse cultural forms.’ (The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History, p. 77) We need to look like the communities we serve in all areas of age and diversity. For the Church of England that means believing in and supporting children and young people in ministry; facing up to our own failings to welcome and include many under-represented groups, particularly people with disabilities and those from a Global Majority Heritage; and committing ourselves to the current Living in Love and Faith process and our already agreed pastoral principles so that LGBTQI+ people are in no doubt that they, along with everyone, are equally welcome in the Church of England. It also means putting renewed resources into our poorest communities.

Whilst some have questioned why we only have three priorities, they are, I believe, vital for the Church of England in the 2020s as we continue to serve Jesus in the power of the Spirit through his Church.

In 2 Corinthians, the apostle Paul writes, ‘if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation.’ Our desire is to reach everyone with the good news of Christ, and especially those who in the past may have felt excluded. That is why the work with racial justice, a new bias to the poor, and an emphasis on becoming younger are so important.

Ultimately, this vision flows from the joy we find in the risen Christ. It is an Easter message. A message of transformation for the world, as a church that is renewed and re-centred in Christ and shaped by God’s agenda for the world will be good news for that world. It will bring God’s transformation to the hurt, confusion, weariness, and despair we see around us—that Church existing for the benefit of its non-members as Temple so memorably put it.

More blogs on religion and public life

- Faith and Voting: The UK general election 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Labour and Faith – Brave New Reset or Faith-Washing?

by Chris Baker - Lessons for an election year from the Bishop of Unity

by Ian Mayer - Food, hope and love: the local church in a time of crisis?

by Paul Monk - Radical hope in the midst of poverty in the city

by Grace Thomas

1 Comment

Dr Malcolm Rigler

19/04/2022 08:02

For many decades The Church of England has been seen as “The Middle Class at Prayer” . Likewise the Medical Profession – in its attempt to “Respond to Human Need” – has largely attracted students from upper and middle class families. Thank goodness – thank God – that Edge Hill University has taken the lead in trying to attract students from working class and so called “disadvantaged families”. Students who ,in time , will be better able to understand and respond to the “human need” of their own family and friends and folk with a similar social and cultural background to their own. See:

Why students from under-represented backgrounds do not apply to medical school

Ciaran Grafton-Clarke, Luke Biggs, Jayne Garner

Medical School

Research output: Contribution to journal › Article (journal) › peer-review

Overview

Fingerprint

Abstract

Medicine is the most competitive undergraduate course at university, and admission processes have been shown to favour those applicants from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Emphasis has been placed on widening participation initiatives to combat this; however, the effects of these have been minimal. Identifying reasons why students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are not represented in the medical school population is the main driver for this study. Using a focus group methodology, pupils from a socio-economically disadvantaged secondary school in the UK were asked about their perceptions and attitudes towards studying medicine at university. Using thematic analysis guided by Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, key areas were identified concerning student views upon perceptions of self, expectations of self, perception of university and the perceived barriers to medical schools. The study has shown a lack of knowledge and guidance in this group of secondary school students, suggesting that more innovative methods of outreach are required in order to make medicine a more achievable goal for students from under-represented backgrounds.

My own Background.

When I qualified as a Doctor of Medicine in the early 1970s only 2% of medics came from a working class background like myself now it has risen to 4% !!

Like myself Bishop David Jenkins ( a former Director at The William Temple Foundation) was troubled by this situation. Might The William Temple Foundation now look into this matter and consider the possibility of supporting Edge Hill University Medical School in every possible way ? Surely our Medical Profession needs “to be re-created” TO BETTER SERVE the people living in the UK ! After all as Sir Kenneth Calman- former Chief Medical Officer of Health in London has so often stated “You cannot and should not attempt to separate – Politics , Religion and Medicine” !!

Discuss this