William Temple scholar Val Barron reflects on the importance of both giving and receiving in light of a recent event on gift-giving.

I’m blinded by your grace

I’m blinded by your grace, by your grace

I’m blinded by your grace

I’m blinded by your

These words have been playing constantly in our home since Stormzy (the first black solo British artist to headline Glastonbury) told the crowd that they were going to ‘take this to church’ before singing his hit song Blinded by your Grace. Suddenly, my teenage son’s eyes were opened to the possibility that faith could be exciting and interesting; and we have been listening to it ever since.

So, it was with this earworm in mind that I arrived to co-host an event this week with Professor John Barclay, Lightfoot Professor of Divinity at Durham University.

In his recent work Paul and the Gift, Barclay offers a sophisticated analysis of grace (gift) by examining the concepts of gift and gift-giving in the ancient world. Barclay argues that the notion of a free gift (without prior conditions, and with no strings attached) is highly controversial because it demands no response. Instead, he suggests, there is an expectation of reciprocity in God’s gift of Christ: “God’s grace is designed to produce obedience, lives that perform, by heart-inscription, the intent of the Law”. Giving a gift creates a relationship, and therefore there is an expectation of a response. God gives freely, but a response is required—a response that entails our fulfilment and flourishing. Without a response God’s love does not cease but it is not fulfilled.

Paul was fundamentally concerned with creating new communities that crossed ethnic and social boundaries. He expected gifts to flow in all directions, including straightforward exchange between givers and a more general reciprocity. We are not designed to be self-sufficient. The gifts in the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12, Romans 12, Ephesians 4) all have something to contribute—with privilege and dignity attached to being the giver. We are all vulnerable, and we all need others in one respect or another.

The ethos of koinōnia i.e. communion, or participation (Philippians 2.1-5), Barclay reminded us, involves not giving oneself away, but giving up what impedes shared benefit (what is only for oneself) and giving oneself into a shared relationship of co-interest.

At the same event, we also had the pleasure of being joined by Bishop Francis Loyo from South Sudan. Over coffee I enquired how he was finding the conversation. He reminded me of the notion of ubuntu—”I am because we are“—the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity. In his home, he said, it was impossible to survive alone; human reciprocity was necessary for survival.

I found myself wondering: could koinōnia or ubuntu be a theological basis for Asset-Based Community Development which seeks to reorient theory and practice from community needs, deficits, and problems to a focus on community skills, strengths, and power (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993)? Perhaps koinōnia goes even deeper and further than models of Asset-Based Community Development? It seems to involve a gift-partnership where we all share in the giving and receiving rather than simply building on the gifts of ‘others’. As Paul wrote to the Galatians:

Love, serve, correct, welcome one another: the power of being host is distributed; ‘bear one another’s burdens’ (Galatians 6.2)

Furthermore, what does this mean for our church social action, where our giving and service is typically a ‘one-way gift’? How can we build koinōnia or ubuntu communities? Can we enter into gift-communities in which we receive as well as give?

Many people attending the event were involved in activities that were ‘serving their communities’, whether lunch clubs, refugee drop-ins, foodbanks or toddler groups. How could we shape this valuable ministry to ensure relationships were central and everyone was given opportunities to give and receive? Is the best model not a soup-kitchen but a pot-luck supper? Are we wrong to push away the offer, when others want to give? Should we allow them to give, as well as receive? It may or may not be right to accept money, but should we be open to other ways in which people can give?

After an afternoon of discussion, we recognised that there were occasions when a one-way gift was necessary (for example initial work with refugees) but that, once relationships are developed, reciprocity and mutuality should be the focus. We discussed how hard this can be and that we have to be willing to take risks and make ourselves vulnerable. It’s much easier for us just to serve our communities, but are we being truly Christ-like?

For example, Pastor Mike Mather’s account Having Nothing, Possessing Everything is a powerful story of a congregation in Indianapolis that stops providing one-way gifts in the form of food pantries and holiday clubs, and concentrates on connecting people in order to allow the giving and receiving of gifts.

The main question I came away asking was: how does gift exchange work within a social enterprise model?

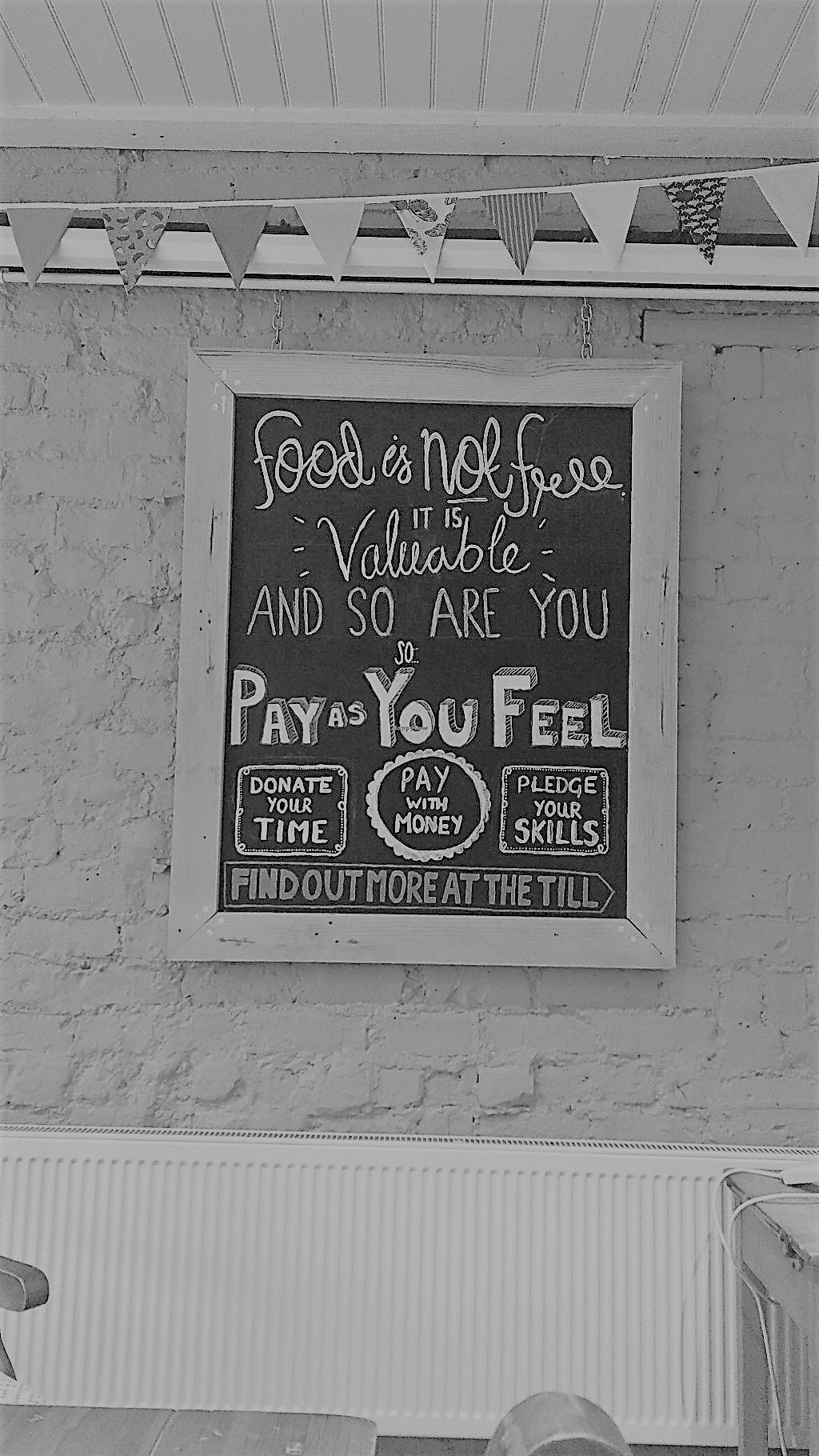

The local community cafe Refuse uses the notion of gift-partnership. Set up as a social enterprise in response to food waste, they receive gifts of perfectly good food that is destined for landfill and use it in their cafe. Visitors are offered options of how to give, allowing those with varying amounts of time, money, and skills to become part of this growing and diverse community.

Every once in a while, you learn something that causes you to re-evaluate your beliefs, values, and practice. The day was punctuated by a hum of ‘aha’ moments and I drop home singing Blinded by your Grace slightly differently.

More blogs on religion and public life…

How to debug theology? by John Reader

Lies and damned lies about statistics by John Henry

Flexible and audacious hope in a tumultuous world by Chris Baker

Whose “bloody GDP” is it anyway? by Tim Howles

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this