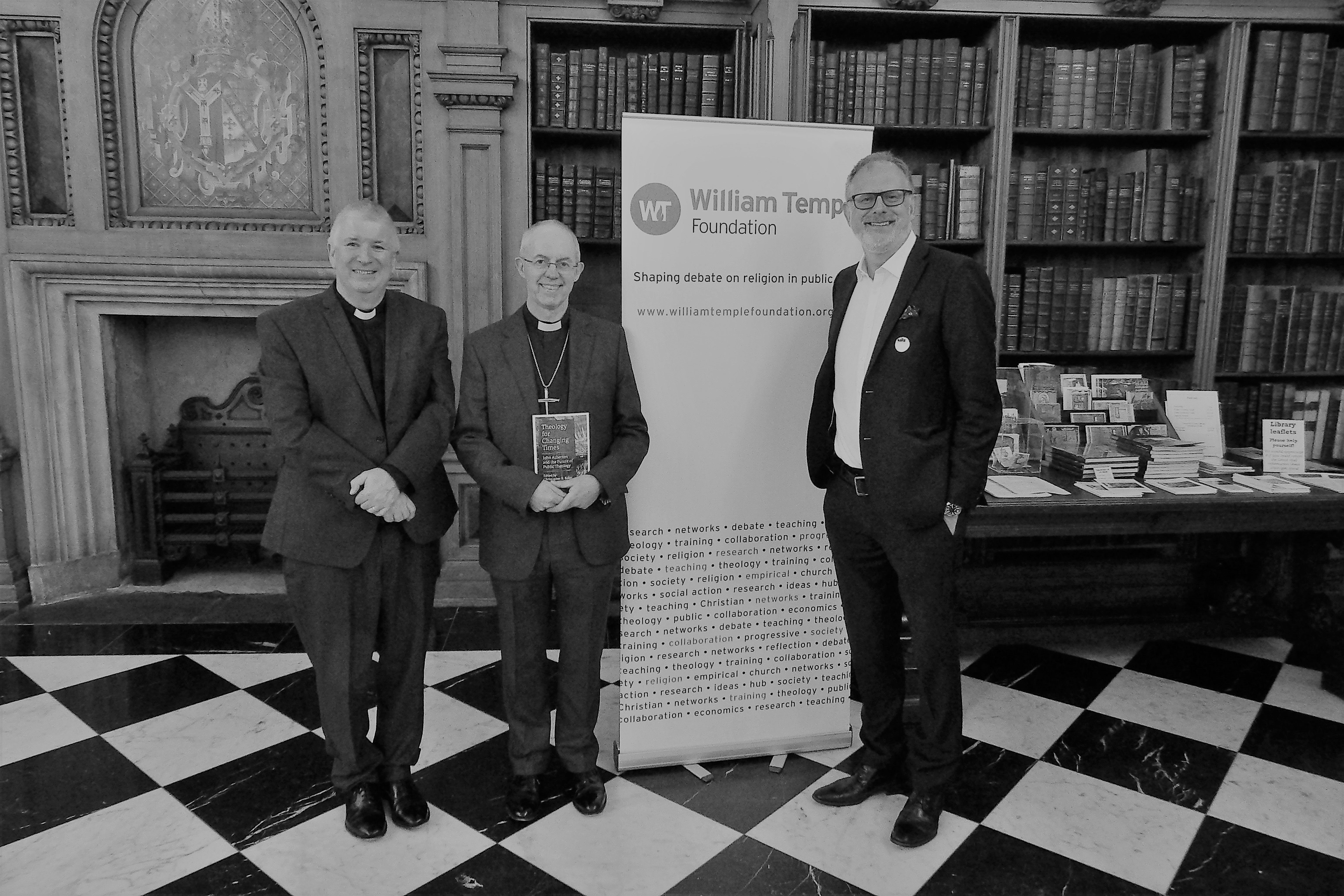

Professor Chris Baker, Director of Research at the William Temple Foundation, reflects on our 2019 annual lecture by Archbishop Justin Welby.

Watch the whole lecture on YouTube here

In a virtuoso William Temple Foundation annual lecture last night, Archbishop Justin Welby laid out a realistic but hopeful assessment of the state of the nation, the place of the church and religion, and the prospects for a revitalised social and public sphere. It was a lecture brimming with intellectual and theological ideas, but also characterised by down-to-earth and personal anecdotes.

The lecture’s wide-ranging reference points were held together throughout by a metaphor, derived from Archbishop Justin’s earlier career, of an oil rig in tumultuous seas with the ‘barometer rapidly falling’. The key to structures like oil rigs surviving raging storms is to maintain an equilibrium between stability (or inner coherence) and flexibility—between anchors and movement. Too much rigidity from the anchors tying it down, and the system will not be able to bend; too much flexibility, and the structure will be unable to withstand the forces placed upon it.

Of course, this metaphor could apply to church institutions, like the Church of England itself, but it could also refer to other political, public, and private institutions—and indeed nations. The Archbishop’s analysis was that too many years of complacency, fostered by the success of the post war-welfare state and Bretton Woods arrangements—anchors which provided a sense of stability and order—have led us to forget the importance of anchor institutions and ideas, and how they can represent things beyond themselves, like the notion of a more common good.

But the global financial crash of 2008/9 changed everything. When that storm came, the resilience in our institutions wasn’t readied, or its need anticipated, and we have been playing catch-up ever since. Into this vacuum, Archbishop Justin reflected, we have seen the rise of both nationalism and populism which have become narrow in their scope and intimidatory intent. Part of the rise of these narratives is attributable to broader changes in technology and the growth of digital and social media. At its best, social media creates spaces for people to explore, discuss and organise. But at their worst, these spaces expose us to ridicule and abuse that sees ‘diversity as a menace and disagreement as a threat’, in ways that are increasingly unaccountable. The Archbishop finished this compelling analysis with reference to two key thinkers, Friedrich Nietzsche and Carl Schmitt, who argue that the ‘will to power’, and the categorisation of another as your enemy, are essential to the formation of identity. These ideas now have dangerous social resonances at a time when people feel their sense of stability and identity to be most under threat.

In the final third of his lecture, Archbishop Justin asked: ‘Can Faith be an anchor in a world of stormy change?’. The answer is Yes, provided it can be alive to the possibilities of ‘traditioned innovation’—returning to core basics, but in ways reflecting what Archbishop Michael Currie refers to when he says: ‘Often change is not about discarding the past so much as revisiting it in a new way for a new time’. For Archbishop Justin, this refers to three core tasks that lie at the heart of Christianity’s call to engage with the public square.

The first is prayer, which ‘relates the common good as we experience it back to the source and origin of all good, namely God and which places all our relationships into a common and wider humanity’.

Second, living out the intent of our prayers as a form of embedded community in ways that model authentic alternatives to our ‘hyper-individualised modernity’ through recognising, in the words of the recently departed Jean Vanier ‘that we are strongest when we recognise our interdependence, not our independence’. The role of the church, along with the temple, the synagogue, and the mosque, the Archbishop said, echoing the words of William Temple, is to exist as the ‘fundamental intermediate institution’.

Finally, there is a mandate to live out individual and community expressions of prophetic action; speaking out against injustice, and symbolically enacting alternative Kingdom values. The Archbishop highlighted the recent intervention by Pope Francis as a good example, when he kissed the feet of the leaders of the warring factions in South Sudan.

What particularly struck me, however, was that the Archbishop never once mentioned Brexit. And yet this was the stunning achievement of his lecture. He spoke ‘into’ Brexit without referring to it, with compassion, clarity, and vision, by recognising that the sources of hope and reconciliation we need as anchors far outweigh in their import, necessity, and timelessness, the temporary albeit very dangerous realities that Brexit embodies at this time, not only for the UK, but also for Europe as a whole.

I for one caught a welcome glimpse of a post-Brexit future. For this reason, this lecture was able to raise its gaze to deeper and longer lasting sources of ethics and values in the service of that future, and, above all, to practical sources and expressions of hope by which we can re-imagine Britain, and a more common good.

More blogs on religion and public life…

Whose “bloody GDP” is it anyway? by Tim Howles

Come the Resurrection…? by Rosie Dawson

Chinese Christian Schools in the 21st Century by Oscar Siu

Tell the truth and act as if the truth is real by Matt Stemp

More blogs on religion and public life

- Assisted Arguing

by Simon Lee - Reweaving the fabric of society: partnership working with the faith sector in Lancashire

by Peter Lumsden - How the Questions we ask are helpful in viewing the world in a different way.

by Ericcson Mapfumo - What Southport does today, the whole country could do tomorrow

by Simon Lee - The Unexpected (And Undiscovered) Public Goods of Video Games

by Andy Robertson

Discuss this