Ben Thompson, an ordinand at Ripon College Cuddesdon, writes about the post-lockdown return of music to our churches. But why did we miss it so much?

When we listen to music in Church, are we engaging with God, or are we being emotionally manipulated? As a musician whose life has been characterised by music within churches, this is a regular question I find myself considering. When I’ve left services feeling elevated, the music has often been produced to a good quality. When I’ve left feeling flat, often the music has left much to be desired. Friends and family have talked about these occasions in the language of religious experience. But I’ve always felt slightly conflicted.

As churches have adjusted to the effects of COVID-19 it is clear that the absence of music within worship has created a sense of loss for many. As musicians have returned to their duties, many have spoken of a sense of joy, whilst the Revd Marcus Walker has spoken of ‘tears’ as his choir performed Parry’s ‘I Was Glad’. But where did our sense of loss come from in the first place? Was it the denial of a religious experience, or the lack of an emotional response? Perhaps this is an opportune moment to consider what it is about music which makes it so important for many Christians’ engagement in worship.

Music and religion have always enjoyed a symbiotic relationship. This should perhaps be unsurprising. It is the ethereal manipulation of air in communion with all that is ethereal. Such is this relationship that Christian thinkers have even been able to locate God in non-sacred music. For Karl Barth in the twentieth century, for example, Mozart’s symphony in G minor conveyed the totality of God’s creation. For Rob Bell in the twenty-first century, God is to be found in a Rolling Stones gig. For many, the combination of harmony, melody and rhythm are foundational to their relationship with the creator of these things.

And yet, for more than half of Christian history, Christian music involved no harmony (or at least, no harmony as we understand it). The evidence suggests that until the twelfth century there was only ever a single melody line. Whilst this doubtless had an emotive effect on our forebears, the strength and power of the sound could not compare with that of the last four hundred years. The saints of the first millennia would have felt very comfortable with the audio arrangements of many churches as they returned from lockdown.

But maybe we could assume that progress in music is a gift of God? This may or may not be the case, but the discerning Christian should question whether sensations that occur during worship are a direct spiritual connection with the Godhead or are representative of something else. The psychologists Carol Krumhansl and Nikki Rickhard believe that music creates the same physiological responses within the brain as other emotions, and this has been evidenced by research by Louis Schmidt and Laurel Trainor, amongst others. To put it another way, when we feel an emotional response to music, it is because our brains are reacting as if we were engaging in real-life circumstances that cause those same emotions.

Research by Hussain-Abdulah Arjman, Jesper Hohagen, Bryan Paton and Nikki Rickard has demonstrated that the brain responds with in an identical way to natural emotions when features within a piece of music change. I suspect many musicians would instinctively understand this. Guitar or keyboard driven bands I’ve performed with understood that changing the volume or harmony in a song is ‘powerful’. Many worship songs leading into a time of prayer will suddenly drop in volume for the last chorus in order to create a prayerful atmosphere.

Such musical manipulation does not only apply to modern musical styles; when I used to conduct bands in The Salvation Army, I could communicate musical decisions to twenty-five players which would create an emotional journey in the hymns of Charles Wesley. I know organists who understand how to do similar. Many feel a heightened sense of excitement in descant verses in Christmas carols, as the organist pulls out all the stops and the altered harmony builds the tension until the release of the final chord.

So, as we clamour to return to our musical activity, I find myself asking: what is it I want to restore? The communal act of worshipping God as a sacrifice of praise, or the emotional sensations experienced as a result of Church music? Whilst I hope that God uses the combination of sound, psychology, and the decisions of musicians in order to create religious experiences, perhaps this time of adjustment should be causing those responsible for music in churches to pause and reflect. If we know emotions can be affected, we should be thinking very carefully about whether we’re trusting God to work through music, or whether we’re trying to control the emotional atmosphere ourselves.

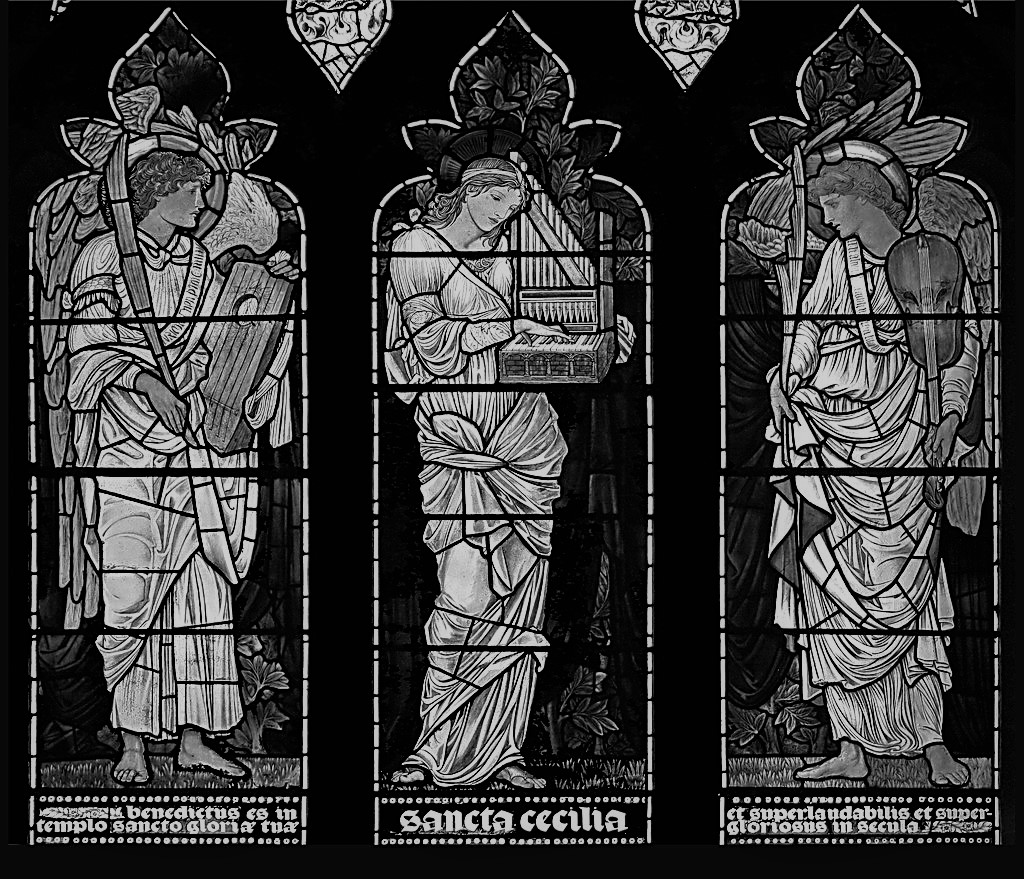

Image: “St Cecilia window” by Lawrence OP is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

More blogs on religion and public life…

Is XR undergoing a just transition? by Matthew Stemp

Review of ‘Christian hospitality and Muslim immigration in an age of fear’ by Matthew Kaemingk by Greg Smith

Review of ‘Future Politics: Living together in a world transformed by Tech’ by Jamie Susskind by John Reader

On your bike: exploring the relationship between obesity, poverty and inequality by Gill Reeve

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this