This week’s blog comes from Dr Karen Lord, a member of our William Temple Ethical Futures network. Dr Lord is an award-winning author whose writing focusses on possible futures and alternate worlds. Here, she recounts the disturbing experience of a fiction that is rapidly becoming fact.

Last year, I was asked to write a story about the future of health. Speculating about the future is my job, but for something this specific and important, I asked Dr Adrian Charles to be my advisor for all things medical. We chose that perennial favourite of history and fiction—a pandemic—never guessing that within weeks of the story’s publication, history would become present, and fiction real life.

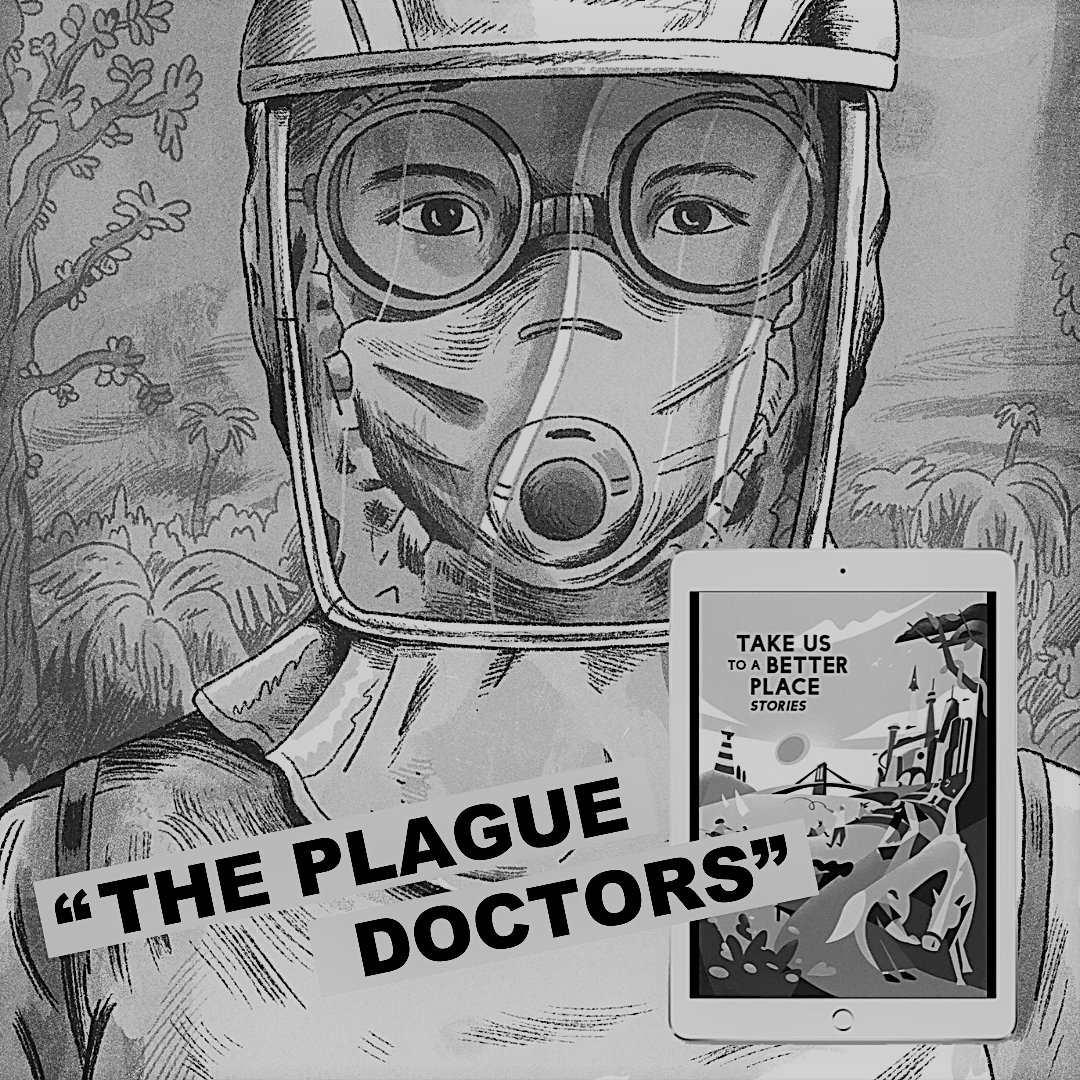

Take Us To a Better Place, a collection of ten short stories from a diverse set of authors, was commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a USA philanthropy, to help readers see how decisions we make today on a range of issues could influence our health tomorrow. The anthology was published on 21 January 2020 and is available free as an e-book in English and Spanish, and in audiobook format.

Roxane Gay provided the foreword. Science writer Pam Belluck, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Ebola, wrote the introduction, which included this summary of my story:

A different sort of dystopia, an uncomfortably realistic one, confronts us in Karen Lord’s “The Plague Doctors.” It is only 60 years from now, and the earth is being wracked by a deadly infectious disease, with bodies from the mainland washing up on an island where Dr. Audra Lee is desperate to find an answer in time to save her pox-exposed six-year-old niece. It’s the kind of global pandemic that should prompt all-hands-on-deck cooperation, but Dr. Lee finds herself working not only against a disease but against a veil of secrecy and selfishness erected by wealthy elites who want to prioritize a cure for themselves. Will she be tempted to cross the line of scientific ethics to relieve her own family’s suffering?

That’s the story—but stories are icebergs, and below the surface a writer’s choices are complex.

Why, for example, did I choose a place called Pelican Island for the setting? Easy, because the quarantine station for Barbados used to be located on Pelican Island. Why a two-phase contagious disease? In 2015, Barbados experienced an outbreak of a disease new to the region, chikungunya. With no immunity in the population, the workforce was temporarily reduced and slowed by weeks of sick leave (first phase) and months of chronic pain (second phase). I personally experienced chicken pox (first phase) and hope to never experience shingles (second phase). Why a disease that was relatively easy on children but deadly to adults? Dr Charles, my advisor, reminded me about mononucleosis, which can cause mild, short-term symptoms in infancy but result in a serious, debilitating disease for adults.

We assumed, with great optimism, that sixty years into the future our health systems would be so robust that it would take a combination of unknown factors for something as routine as an epidemic to cause worldwide disaster. We decided on a relatively ordinary, contact-transmission, low-mortality first phase to cause complacency; and an unanticipated, droplet-transmission, rapid and deadly second phase to cause panic.

We also added extra challenges, some expected, like political unrest and conspiracy theories, and some less expected, like the partial collapse, or rather sabotage, of telecommunications, leading to restricted access to and exchange of information.

So, how does Dr Audra Lee fight a pandemic on limited resources? We added critical background details, like a second, smaller island for quarantine and a coast guard on constant patrol. Futuristic tech is available, such as advanced 3-D printers to manufacture on-island equipment that can no longer be imported, for example, bespoke parts of the personal protective equipment. We settled on a contemporary design for the PPE. The illustrator, Niv Bavarsky, produced an accurate image of suit, goggles, mask, and face shield, which is now all too commonly seen on the news.

Audra can also rely on the main hospital, but her best support is the island-wide network of community health teams to which she belongs—quasi-mobile units that include one or more doctors, nurse practitioners, caregivers, counsellors, nutritionists/herbalists, lab technicians and pharmacists. The health teams do not merely tend to the sick; they actively monitor the well and reduce the burden on the main hospital by preventing or mitigating illness before it gets to a critical stage. The community model is effective, but the teams’ actions are occasionally questionable, for example, when regulations and procedures are overlooked so that Audra can take care of her niece at home.

For Audra to win the war against the grey pox, it will take the further cooperation of similar community-oriented teams of practitioners and researchers in remote locations around the globe, the IT support of a guerrilla group of techs operating outside of the usual channels, and financing from a few billionaires who have ‘learned the hard way that a luxury bunker is too narrow a world at any price’.

To win our battle against COVID-19, we too will need broad-based support and many heroes. It’s never a comfortable feeling for a writer when fiction strays too close to prophecy, but often what looks like prophecy is merely the skill of reading the signs of the past to guess at the challenges—and solutions—of the future.

More blogs on religion and public life…

Liberty and response-ability in the time of coronavirus by Tina Hearn

My organism knows so much more than I do by Jeff Leonardi

Review of ‘The Road to Unfreedom’ by Timothy Snyder by John Reader

It’s not simply Facebook’s fault by John Henry

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this