Our new William Temple Scholar, Matthew Barber, offers his thoughts on our present politics and introduces the work of Spaces of Hope.

Prorogation of Parliament and the ensuing High Court challenges are the latest act in a Brexit farce that has been running for over three years. The government drive to ‘deliver the will of the people’ clashes with cries of #StoptheCoup, as thousands march, seeking action that curtails the undemocratic heist across, what is for now at least, our United Kingdom.

Our national identity crisis, brought into sharp focus by Brexit, is unprecedented since World War Two. Archbishop Justin Welby reminded us of this in his 2019 William Temple Foundation Annual Lecture, when he compared our present uncertainty to that faced by Temple, Tawney, Beveridge and others as they sought a new political settlement in the 1940s. Building on the legacy of his predecessor, Archbishop Temple, Welby proposed that a similar sense of imagination and holistic commitment could guide us now and galvanise us against the uncertainty we face. Temple was peerless in his combination of social, political and theological disciplines, typified by Christianity and Social Order (1941), offering principles of freedom, fellowship and service to one another, to guide deployment of our different gifts and competencies as a means of mobilising the welfare state. It goes without saying that our world looks very different nearly 80 years on, but synergies abound as we are challenged once again to work for the future of our nation.

But how do we occupy uncertain spaces whilst staying within the law? How do we equitably broker power rather than mirroring the behaviour of our oppressor? How do we embrace the differences that exist at the heart of each of our lives? How can we build bridges and broker peace, to renew the relationships at the heart of civil society, and our nation?

Baker’s, Crisp’s and Dinham’s 2018 work offers a place to begin with these questions, presenting landmark interdisciplinary perspectives on how holistic commitments can shape the public space through policy and practice. A key finding is that ‘liminality’—a term developed by Arnold van Gennep and later by Victor Turner—is emerging as the new norm. Liminality means ‘disorienting and non-binary conditions, where old certainties and hierarchies are suspended until such a time as new resolution and clarity of identity is reached’ (p.30). In the context of Parliament being prorogued and comparisons with World War Two, language of liminality as the new norm conjures a spectre of fear, as darker periods of our history are foregrounded once again. However, out of one of the darkest periods of our history also emerged health, hope and connection across our communities, inspired by Temple and his contemporaries. There are ideas and movements emerging, but the challenge is to connect them.

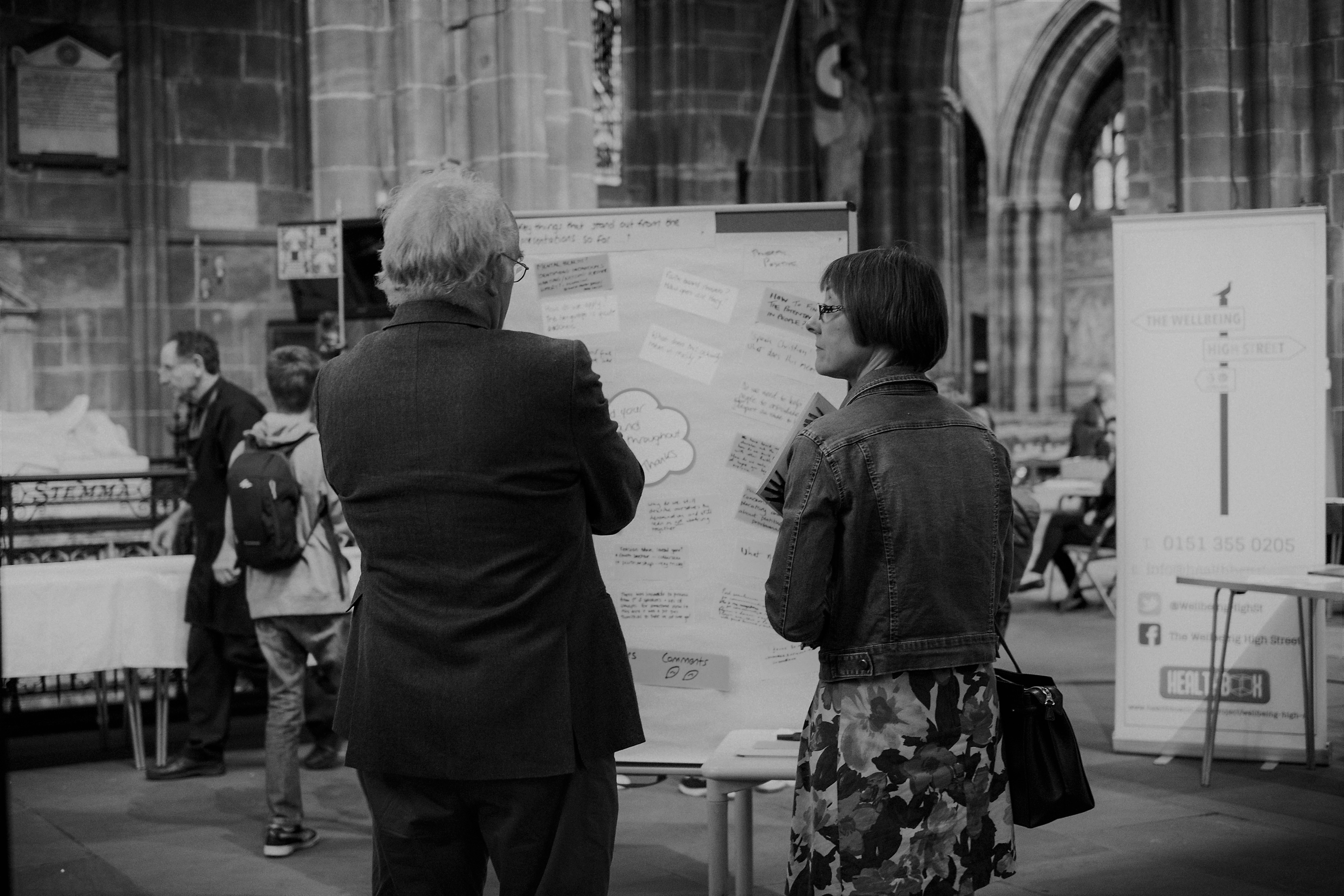

My own work, Spaces of Hope, combines the personal struggle of growing into our world, with the work of Temple, Baker, Dinham and others, within a new organisational paradigm framed by liminality, curating differences at the heart of shared spaces. By reflecting on the laws that govern spaces, power dynamics and social relations Spaces of Hope understands how different beliefs and values, at different scales, expressed through different practices, into different spheres of society, shape spaces, places, people, policy and practice. In the last three years, a quiet revolution has been building in the northwest of England, sharing stories, weaving networks, and curating over 30 gatherings. According to the Inquiry into the Future of Civil Society in England, Spaces of Hope has enabled and emboldened the development of deeply authentic networks and relationships, the drawing out of meaning and values shaping the spaces people are engaged with, before identifying and acting on what this means for community practice.

The Spaces of Hope Hubs Network in the Borough of Stockport in Greater Manchester might be our most significant contribution. The network curated liminal spaces, using dialogue tools to address questions in local communities. Afterwards, we found that 73% thought differently about their own work, with 67% saying that they shared their differences in an open and productive way. 33% said Spaces of Hope had either directly or indirectly enabled them to establish new work. We shared stories about wellbeing and hospitality; weekly intergenerational drop-ins; connection through the pioneering Alvanley Social Prescription programme; and humble refuge, with reciprocal support offered between the homeless, asylum seekers and refugees at a local church. We also asked, what does Spaces of Hope mean to you?—contrasting answers with perceived barriers. Nearly 300 responses revealed that 65% think it is about personal vulnerability, connection and freedom. Conversely, 39.6% saw perceptions of or scepticism towards different cultures, beliefs, values and worldviews as the biggest barrier. 24.8% said they lacked confidence that anything would change. These insights resonate with the divides we are seeing nationally, whilst also revealing the contradictions at the heart of our communities. 90% of attendees found the gatherings helpful and were confident that the Spaces of Hope approach would make a difference over time.

These are just seeds, but they will need a generation of nurture if they are to fully inform a hopeful future for our nation. These seeds include contributions from public institutions, such as the Diocese of Chester, the William Temple Foundation, the Royal Society of Arts, and Stockport Council, alongside people from communities across Cheshire and South Manchester now numbering over 500. What we have found is that Spaces of Hope means different things to different people, but by harnessing differences in liminal spaces we are hearing voices unite and guiding practices that are seeking hope for the future of our communities.

Spaces of Hope dialogues continue during October 2019. Key events coming up include:

- World Mental Health Day and Interfaith Engagement at Manchester Cathedral concluding a Month of Hope by Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership, where a story of hope will be shared – 10th October – Free

- A research colloquium called Grassroots Movements and Partnerships of Hope at Goldsmiths College, where Spaces of Hope will inform dialogue with other emerging movements – 16th October – Free

- A public impact event in Stockport, Curating Spaces of Hope; Exploring the Movement from Root to Fruit, explores the last three years, with a view to shaping the agenda for the future – this is at St Mary’s Stockport – 23rd October – Free

More blogs on religion and public life…

What sort of society do we wish to become? – Borges’ forking pathways by Tina Hearn

Review of ‘Zucked: Waking up to the Facebook Catastrophe’ by Roger McNamee by Maria Power

Review of ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism’ by Shoshana Zuboff by John Reader

Do not despise the day of small things by Gill Reeve

More blogs on religion and public life

- “Barnabas Thrive” led by Revd Dr Paul Monk, is awarded Kings Award for Voluntary Service

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - How could a Temple Tract have had even more traction?

by Simon Lee - Remembrance Day: Just Decision Making II

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Trustees Week 4th Nov – 8th Nov 2024

by Matthew Barber-Rowell - Some ancient wisdom for modern day elections

by Ian Mayer

Discuss this